This is the second part of a three-part series on San Salvador’s Historic Center, the heart of the country’s informal urban markets and a long-time bastion of the street gangs. The stories chronicle how the gangs have used their stranglehold on the center to expand their power in El Salvador. This part explores how the gangs have steadily usurped the economic and political power from the city’s informal vendors’ associations.

On November 27, 2018, El Salvador police operatives sat at a fast-food chicken restaurant in the capital city, San Salvador. They were tracking Vicente Ramírez.

Ramírez was part businessman, part community leader, part politician and, government investigators believed, part gang-affiliate. As part of their investigation, the Attorney General’s Office had tapped Ramírez’s phone several weeks prior to the stakeout. Among those they heard him speak to were members of the notorious Mara Salvatrucha (MS13).

With an estimated 30,000 members in El Salvador, the MS13 is the largest street gang in the country, and it has a strong presence in the city center where Ramírez operates. To be sure, Ramirez had built a career as a defender of El Salvador’s informal economy, including hundreds of street vendors that line the streets of the capital’s Historic Center, the country’s biggest informal marketplace and an important cross-section of gang and political power in El Salvador.

*This story is based on field research spread out over two years, including numerous field visits and dozens of interviews with police officials, police intelligence officers, gang members, municipal and federal authorities, street vendors, community workers, business owners, non-governmental workers and others, most of which were done prior to the coronavirus pandemic. Given the sensitive subject matter, most of the sources agreed to speak with InSight Crime anonymously. Read the entire investigation here, as well as our follow-up article on President Nayib Bukele’s informal pact with gangs.

On that November day, the investigators had sent police agents to the Metro Sur shopping center in San Salvador, just blocks from the city’s Historic Center, to observe a meeting between Ramírez and his supposed gang counterparts.

They sat down at the Pollo Campero, a popular regional fast-food chicken chain with a branch in the mall, and, against a backdrop of multi-colored furniture and cartoon images of poultry, observed their subject engage with two affiliates of the gang.

Investigators later identified one of them, Cristina Esmeralda Vásquez de Grijalva, as the “sister-in-law” of a gang member, Borromeo Enrique Henríquez Solórzano, alias “El Diablito de Hollywood” (Hollywood’s Little Devil). Henríquez is one of the top leaders of the gang in El Salvador. The other person sitting with Ramírez was Ricardo Antonio Lucha Ramírez, an MS13 member, who went by the moniker “Guanaco de Maniacos Cusca.” The investigators took photos as the three spoke.

MS13 News and Profile

By then, the gang and Ramírez had been dealing with one another for years. The gangs in the Historic Center collect extortion from the vendors. But they also keep thieves at bay and resolve disputes. With time, this relationship had evolved, and investigators allege that Ramírez had become more of a partner to the MS13 than a victim of their extortion schemes.

The line is fuzzy, and it was clear from the wire-trappings prior to the meeting in Pollo Campero that the gang members thought Ramírez did not always follow their orders. One member had even threatened the gang would remove him from his position as president of an association representing the informal street vendors. Ramírez, clearly concerned, had asked Vásquez de Grijalva and Guanaco to come to the Pollo Campero to help clear the air. His life’s work, and his possibly his livelihood, were slipping through his fingers.

Ramírez’s pleas were, in a way, representative of a larger shift underway. The gangs had steadily moved from predators to partners. And now they were looking to take the final step: They wanted to be the owners.

Historic Center: Formalizing the Informal

Ramírez, a grey-haired, bushy-eyebrowed man of relatively small stature, has a grand talent for community organizing. He spent decades creating syndicates such as the National Association of Workers, Vendors, Small Merchants and Other Small Businesses (Asociación Nacional de Trabajadores, Vendedores, Pequeños Comerciantes y Similares – ANTRAVEPECOS), which was the group he was presiding over when he met with the MS13 in the Pollo Campero.

The associations oppose state efforts to formalize the makeshift market spaces where informal merchants make ends meet, nowhere more so than in the hustle and bustle of downtown San Salvador. Known as the Historic Center, the city’s downtown is a seven-square kilometer area where you can buy just about anything. From shoelaces to soap to T-shirts to street food to souvenirs, it is all for sale, mostly under the tin roofs of the ramshackle vending spots that spill into some of the city’s main thoroughfares. Other vendors are mobile, selling phone chargers, bananas, batteries, and drinking water, among other products.

In all, there are an estimated 40,000 informal vendors that, prior to the forced quarantine that began with the coronavirus pandemic, would come to downtown San Salvador every weekday to hawk their goods. None of them have official permission, yet all of them carry the world’s most important calling card: the right to earn a living. In El Salvador, over 60 percent of the economy is informal.

The city’s vendors are split into somewhere between 75 and 80 associations. They are led by people like Ramírez – experts in rallying protests against government attempts to tax and displace the vendors – whose experience dates back to when the street sellers first arrived in El Salvador’s main cities. The country has lived through an urban boom. In 1970, just under 40 percent of El Salvador lived in cities. By 2019, that number was over 70 percent, according to World Bank figures.

Over time, the informal has become formal, and by the early 2000s, thousands of people were traveling to the Historic Center from all around the country to make a living, often on the streets selling low-priced goods, contraband or stolen items.

Many of them brought their children, who joined the fledgling gangs emerging in their poorer neighborhoods and the downtown area. These gangs operated under the umbrellas of two US-born gangs – the MS13 and the Barrio 18. They were both led by criminal deportees from the United States and took on the names of parks, streets or their neighborhoods.

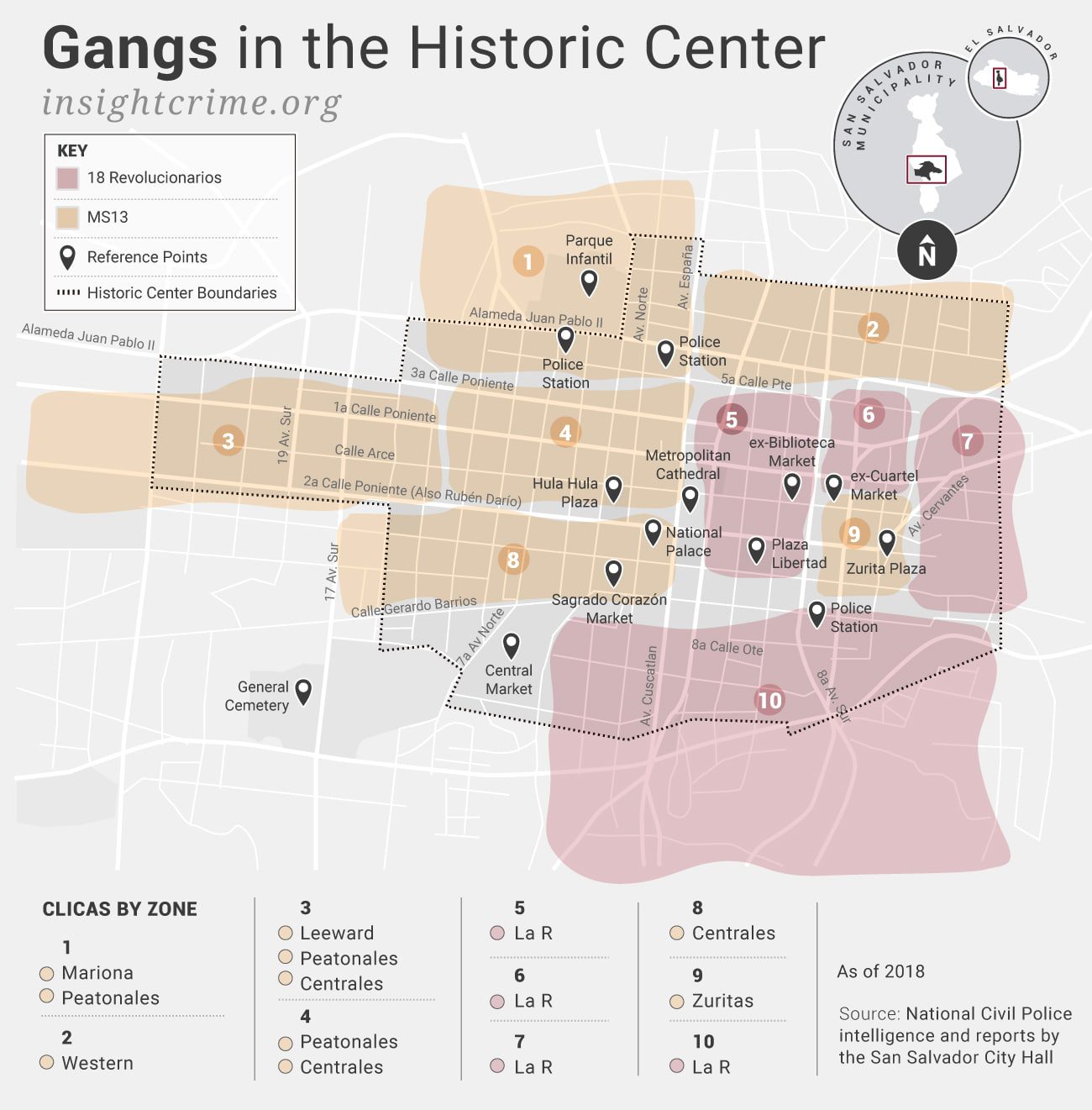

Eventually, the two processes overlapped: vendors spilled into the streets; the gangs – specifically the MS13 and one faction of the Barrio 18 known as the Revolucionarios – spilled into the Historic Center’s vibrant underworld.

For street vendors, this has come at a cost. In the MS13 areas, the gang charges vendors in the Historic Center with a fixed position an average of $1 per day, according to multiple interviews with gang members of the MS13 and Barrio 18, vendors, storefront owners, business associations and security officials.

There are slight variations to this amount. These differences depend on what some police and business associations referred to as “commercial flow,” or the amount of perceived sales. Clothing or shoe retailers, for instance, could pay as much as $10 per week.

In the Barrio 18 areas, the collection system is based on space occupied rather than “commercial flow.” Police intelligence sources in the Historic Center told InSight Crime that it costs vendors $1 per square meter. They pay an extra $2.50 daily per square meter for “cleaning” and “security.” This is managed more directly by the vendors’ associations who also rotate collectors to keep authorities guessing. A vendor operating in the area where the Barrio 18 holds sway confirmed these figures.

There are exceptions to this “rent” system. According to vendors, business association leaders, and police, street vendors that are relatives of gang members very often do not pay. Smaller, mobile vendors without permanent posts can pay as little as $0.25. Many sources said that the mobile street vendors were either gang members or collaborators, used as a means of keeping control and close watch over the vendors. Their closeness to the gang can also make mobile vendors de facto interlocutors when there are problems between the vendors and the gangs, police and local shop owners told InSight Crime.

The gangs guarantee the payments through a mixture of threats, beatings, and the fear of murder for those who fail to pay. It is, as one local business association head described, a kind of “parallel state.” The revenues are enormous, upwards of $40,000 per weekday or about $1 million per year for the gangs’ coffers.

A Symbiotic Relationship

According to El Salvador’s special prosecutor in charge of extortion cases, Álvaro Rodriguez, Attorney General’s Office investigators listened to Vicente Ramírez’s phone calls with members of the MS13, and they determined he was working with the gangs. Specifically, they said he was passing messages between incarcerated gang leaders and the leaders on the outside of prison. And in one particularly revealing call, Ramírez is heard telling a suspected gang member, “Man, I am collaborating with the gang a lot.”

Investigators said Ramírez was also among several association leaders allegedly helping the gangs collect extortion payments. The collection system – according to police intelligence, vendors, and businessmen consulted for this report – is dependent on the vendors. To collect extortion from the street vendors, for example, the leaders of the MS13 designate a lieutenant who is responsible for the management and administration of these areas. These lieutenants work through intermediaries, often called “block captains,” who have varying relationships with the gang ranging from member to relative or acquaintance to someone completely outside of the gang structure. But much depends on the amount of influence the gang wields in the vendors’ associations in that area.

The vendors roll the money tightly before passing it to the block captain, these same sources say. The block captain puts the money into a plastic bag. Once the captain has collected all the money, it is passed to a designated gang member. It’s not clear if the gang lieutenant receives the payment from each of the block captains individually, through an intermediary or from other gang members. The block captain can also be fixed or rotate. Rotation is preferred since it spreads the risk and makes it harder for authorities to disrupt criminal activity.

On one level, having an elaborate system that went through the vendors was not surprising. Prior to the gangs’ arrival in the Historic Center, the vendors’ associations collected payments from their members. Now, prosecutors thought Ramírez and others were doing it for the gangs.

Still, discerning between victim and victimizer can be difficult in these situations involving gang extortion, especially in the case of the informal vendors in the Historic Center. The special prosecutor Rodríguez was quick to point out that figures like Ramírez “do not represent the majority of vendors,” who are mostly forced into paying gang extortion, but rather “they respond to the interests of the MS13 cliques.”

But while the relationship between the street gangs and the street vendors could be parasitic, it could also be symbiotic.

To begin with, the gangs keep some forms of predatory delinquency to a minimum and keep payment and protection systems simple for their constituents. They have done this by effectively banning any competition from their areas of influence and prohibiting predatory activity by those who operate in their areas of influence. Violators, both within their organizations and outside, are dealt with severely.

Remarkably, informal street vendors, shop owners, commercial associations, and police all told InSight Crime that was little to no petty theft in the Historic Center, and little breaking and entering. There were also few reported assaults. The police assigned to track petty crime told InSight Crime that the few victims of assaults in the Historic Center were people who were visiting the area, not those who worked there regularly. The beneficiaries of this system are not just the informal vendors but formal vendors, the police, and ultimately City Hall itself, which can claim lower crime rates.

El Salvador Gangs Influence Local Politics in the Capital: Report

Gangs also act as intermediaries in disputes between informal vendors jockeying for space in a competitive environment, the vendors told InSight Crime. And vendors in the formal sector said the gangs resolve disputes when, for example, informal vendors encroach on their entrances or urinate around their storefronts.

Perhaps most importantly, the gangs have helped blunt City Hall’s long-time goal of massively displacing the vendors and formalizing the Historic Center’s economy, thus keeping tax collectors and regulators at bay. This is because the gangs themselves have evolved into a formidable political foe, in part because of their relationship with vendors like Ramírez.

A Seat at the Table

Crucial to the success and survival of vendor association leaders like Ramírez is knowing how to leverage the informal economy’s political capital to increase its bargaining power vis-à-vis the state.

This is nothing new. Early on, the associations realized that in addition to economic clout, they wielded considerable political influence. The vendors hail from nearly every corner of the country, thus any political party interacting with them in San Salvador could also reach those places to secure votes.

The politicians range from local mayors to national assemblymen to would-be presidents. Ramírez allegedly received a salary from a local congressman for a time, according to one rival vendor association leader and police intelligence sources. Others regularly corral votes both directly from their constituents and indirectly with their presence on the streets.

The parties could also mobilize the vendors en masse, as they could any union. And vendors were not afraid to mix it up with authorities and snarl public transportation when they were unhappy with public policy. Their protests have often descended into violence, characterized by rock-throwing and tire-burning, on one occasion landing Ramírez in jail for aggravated threat and public disorder after a ruckus in a town just outside the capital.

This jockeying for space and power became even more volatile after the arrival of the street gangs. In a short time span, the MS13 and Barrio 18 had their own political awakening. Much of it began in the jails, where they were incarcerated en masse beginning in the early 2000s. Coordinated riots and violence forced authorities to separate the gangs. These were soon followed by interactions with non-governmental organizations, church leaders and political parties. In 2009, the gangs held their first collective strike across more than a dozen penitentiaries, demanding better treatment and conditions inside the prisons.

In 2010, to protest further proposed hardline anti-gang laws, the gangs organized a general strike, paralyzing the country’s public and commercial transport services for two days. At the same time, they began negotiating with the government to release some of their leaders from a maximum-security prison. The process culminated in a secret, albeit short-lived, gang truce: an armistice between the country’s three main gang factions that began in March 2012 and led to a drastic reduction in homicides during the 18 months or so it continued to be enforced by gang leaders in jail and police outside of jail.

Among those at the forefront of the truce were gang leaders who had business interests in the Historic Center, such as Henríquez, the same El Diablito of the Hollywood Locos Salvatrucha whose emissary had met with Ramírez. In part, the leaders’ clout came from the vast revenues they secured by extorting the informal vendors.

Added to that were the revenues from extorting legitimate, brick-and-mortar businesses, as well as collecting quotas from drug and illegal alcohol sales, prostitution, and the sale of stolen goods. The Hollywood clique’s presence in the city center, for instance, dated back decades when, in the early 1990s, it stole cars and resold them and their parts in the area.

The gangs also leveraged the informal vendors’ contacts with officials. Ramírez, like his other vendor association leader counterparts, became the key interlocutor between city officials and the gangs while Mayor Nayib Bukele’s administration was trying to implement business development plans in the Historic Center, according to a former official from that City Hall working team.

Ramírez and his counterparts used that leverage to get a valuable seat at the table with city officials during this complex process. City Hall eventually peacefully moved thousands of vendors and revitalized important sections of the Historic Center, the gangs increased their political capital, and Ramírez and his counterparts protected their constituents from being cut from the lucrative markets and vending spots.

The revitalization project also set Bukele up for a run at higher office. The mayor, who had dramatically left his political party during his time in office, was positioning himself for a run at the presidential palace. And with elections around the corner, the symbiotic relationship between informal vendors like Ramírez and the gangs was about to deepen even further.

Informal Campaigning

Among the allegations against Ramírez, recounted to InSight Crime by the Attorney General’s Office, is the accusation that the syndicate leader was part of the chain of communication between the gang’s so-called “ranfla histórica,” its historic leadership council, and the outside world. The ranfla histórica currently operates from within the Zacatecoluca prison. “Zacatraz,” as it is euphemistically referred to in homage to the now-closed US prison in the San Francisco Bay, is El Salvador’s only maximum-security prison.

This communication is a lifeline for gang leaders. They use it to coordinate criminal schemes, such as extortion, drug peddling and car theft; manage their cliques, issuing “green lights” for murders, resolving internal disputes and distributing proceeds; and keeping in contact with their extended families who, as is illustrated by the case of El Diablito de Hollywood, can play key roles in their operations.

By 2010, the prison regime had effectively cut the gang’s communication channels, and one of the ranfla’s demands during the 2012 gang truce was to get moved temporarily to another prison where it could reestablish command and control over its rank and file inside and outside of jail. After the truce ended and fighting between government forces and the gangs intensified, the “ranfleros” (gang leaders) were sent back to Zacatraz where communication with the outside again became a challenge.

Investigators say this is where people like Ramírez came into the picture, helping to pass messages from the ranfleros, whose most prominent member is El Diablito de Hollywood, to the Centrales Locos Salvatrucha clique, the most powerful MS13 cell operating in the Historic Center.

“Let’s say the Ranfleros in Zacatecoluca were sending a message. They would send it via the wife, or partner, of El Diablito de Hollywood. She would give it to her sister, and her sister met meet up with Vicente Ramírez, and from there he went and passed on the communication,” the special prosecutor Rodríguez told InSight Crime.

Awash with street merchants and with a thriving illicit weapons and counterfeit cigarettes market, the area is not just a gold-mine for extortion, it is a source of financial prowess and political capital for the Centrales and their leaders who have also positioned themselves in the upper echelons of the gang hierarchy. The Centrales have as many as 50 cliques with hundreds of members at their disposal, according to police.

In other words, Ramírez had seemingly become a middleman between the MS13’s most powerful members in the jails and one of the gang’s most important cells in an area pivotal to its finances and illicit operations.

The wire-taps and surveillance also established that Ramírez was as an “intermediary between the gangs and figures within City Hall and others that were already in the early stages of elections for the central government,” special prosecutor Rodríguez told InSight Crime.

Ramírez’s alleged meetings included one with these “City Hall figures” in the wealthy Santa Elena suburb of San Salvador, on the evening of December 18, 2018, in the run-up to the February 2019 presidential elections. That night, with police operatives watching, Ramírez and other associates were inside a minimart of a gas station when, just after 6:30 pm, a black Toyota pick-up arrived with two other cars and parked at the station.

The passengers of the Toyota got out, entered the minimart and approached Ramírez and the others. The police, meanwhile, ran the vehicle through their database, according to extracts of the Attorney General’s Office judicial file against Ramírez. The car belonged to Ernesto Sanabria, at the time a press liaison for Nayib Bukele’s presidential campaign team. He is now the presidential press secretary.

Police agents continued watching as the two groups spoke, then got into their cars again and went to a house in a nearby neighborhood. When the Toyota arrived at the house, operatives took photos as the passengers from the pickup, including Sanabria, got out and went inside, along with Ramírez and the other members of the convoy.

Losing Control?

The Attorney General’s Office did not tell InSight Crime what Sanabria discussed with Ramírez that night, other than to say that the objective of the meeting was to seek support for elections. And Sanabria did not respond directly to InSight Crime’s request for comment on the meeting.

It also wasn’t clear if Ramírez was acting in his association’s interest or the gang’s interest or both. By then, Ramírez had arranged meetings and phone calls with candidates from various parties, according to some case file extracts shared by the Attorney General’s Office. His goal, according to the files, was to trade votes for benefits for his vendor’s association, including trying to secure an ally with a post in El Salvador’s Justice and Security Ministry. It’s not clear if that ally ever got the post.

But for prosecutors, it was part of a pattern of illicit activity. The Pollo Campero meeting illustrated how deep Ramírez had fallen into the hands of the MS13. More proof followed. In November 2018, a member of the Centrales Locos clique called Ramírez to tell him that he had found potential candidates for the board of directors at ANTRAVEPECOS, the association that Ramírez directs, according to the same Attorney General’s Office judicial file.

Minutes later, the same gang member phoned Ramírez again, this time to ask for details on the payments the latter was administering within the vendor association. Around the same time, the gang also threatened Ramírez when they thought that he was collecting payments without their authorization, as per the Attorney General’s Office reports.

Ramírez was not happy either. Within the phone-tapping records, there is evidence that Ramírez complained to the “sister-in-law” of El Diablito de Hollywood about the issues he was having with the gang.

In fact, this pact with the proverbial devil had already had significant costs for Ramírez and many other vendor associations who, either due to threats or because of self-interests, had come to similar arrangements with the gangs.

Throughout the Historic Center, both the MS13 and the Barrio 18 have steadily infiltrated vendor associations’ leadership, usurped prime selling spots, taken over and established restaurants and encroached on the lucrative contraband economy. And Historic Center vendors, shop owners, and authorities say the gangs are now “encrusted” within the vendor associations.

According to several police intelligence sources, as well as local business association leaders and former City Hall officials, in some cases, the gangs assign leadership positions to their own members, relatives and associates. That was exactly what seemed to be happening to Ramírez in real-time at that meeting in the Pollo Campero.

He was not alone. At least one other association leader shared an office with a gang, police sources told InSight Crime. Others are now run by gang proxies. And in private conversations with InSight Crime, several leaders of vendors’ associations have begun to wonder whether it is now only a matter of time before the gangs take complete control of them.

In April 2019, during an Attorney General’s Office and police operation aimed at breaking up gang structures operating in San Salvador and other parts of the country, Ramírez himself was arrested and charged with belonging to illicit groups, along with 211 others detained for their suspected involvement in homicides, extortion and drug trafficking. Now awaiting trial, Ramírez could face three to five years in prison for his alleged role as a gang collaborator, according to the special prosecutor Rodríguez.

Both Ramírez and his lawyer, Jorge González, have denied the charges against him, the latter saying that all of his client’s meetings took place within the bounds of the law. But his legal troubles are a clear sign of how the importance of the gangs as political actors in the Historic Center has pushed the vendors deeper into the hands of these criminal groups.

*Additional reporting by César Castro Fagoaga and Juan José Martínez d’Aubuisson.

**This is the second part of a three-part series on San Salvador’s Historic Center, the heart of the country’s informal urban markets and a long-time bastion of the street gangs. The stories chronicle how the gangs have used their stranglehold on the center to expand their power in El Salvador. This part explores how the gangs have steadily usurped the economic and political power from the city’s informal vendors’ associations.

This story is based on field research spread out over two years, including numerous field visits and dozens of interviews with police officials, police intelligence officers, gang members, municipal and federal authorities, street vendors, community workers, business owners, non-governmental workers and others, most of which were done prior to the coronavirus pandemic. Given the sensitive subject matter, most of the sources agreed to speak with InSight Crime anonymously. Read the entire investigation here.

Main Photo: Salvador Meléndez