The Mara Salvatrucha, or MS13, is perhaps the most notorious street gang in the Western Hemisphere. While it has its origins in the poor, refugee-laden neighborhoods of 1980s Los Angeles, the gang’s reach now spans from Central America to Europe.

While they are largely a predatory criminal organization, living mostly from extortion, the gang’s resilience owes to its strong social bonds, which are created and strengthened via acts of violence against mostly their rivals and one another.

Their activities have helped make the Northern Triangle — Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras — the most violent place in the world that is not at war. In October 2012, the US Department of the Treasury labeled the group a “transnational criminal organization,” the first such designation for a US street gang, but their criminal proceeds do not even approach those of their counterparts on that list.

The US government has since gone one step further, in late 2020 charging over a dozen MS13 leaders in El Salvador with terrorism, marking an unprecedented escalation in the country’s fight against international street gangs.

History

The MS13 was founded in the poor, marginalized neighborhoods of Los Angeles in the 1980s. As a result of the civil wars wracking El Salvador, Guatemala and Nicaragua, refugees flooded northward. Many of them wound up in California, living among the mostly Mexican neighborhoods of East and Central Los Angeles, as well as the San Fernando Valley.

While the Mexican gangs reigned in the local underworld, the war-hardened immigrants quickly organized themselves into competing groups, the strongest of which was called the Mara Salvatrucha Stoners or MSS.

The orgins of the name are still disputed, but “mara” is a Central American term for gang. “Salva” refers to El Salvador. “Trucha” is a slang term for “clever” or “sharp.”

Salvatruchas was also the name given to the locals who fought against William Walker, an ambitious businessman and proponent of slavery from the United States who tried to subdue various parts of Central America with a small army in the 1850s. Walker, after a brief stint as the self-proclaimed president of Nicaragua, was overrun and executed by Honduran locals.

For their part, the Stoners were composed of refugees from El Salvador in the Pico Union neighborhood who spent most of their time listening to heavy metal music, drinking and smoking. With time, the gang evolved, shedding their original Stoner name and image: The MSS became the MS.

The gang’s rivals took note. Conflict between the MS and the 18th Street, or Barrio 18, was particularly fierce in and around Los Angeles. The fighting put the gang on the radar of officials who began to jail them in large numbers in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Inside prison, the MS was forced to bow to another master, the Mexican Mafia, or “la eMe” for short, whose power extended from the jails to the streets. The Mafia’s umbrella, known as the “Sureños,” included many prominent gangs and stretched into much of the southwest of the United States and Mexico.

The MS13’s subservience afforded the gang more protection in the streets and in prison. In return, the MS provided hitmen and paid the Mafia regular quotas from their criminal proceeds. It also added the number 13, the position M occupies in the alphabet, to their name. Thus, the MS became the MS13.

By the mid-1990s, partly as a way to deal with the gangs and partly as a product of the get-tough immigration push toward the end of the presidency of Bill Clinton, the US government began a program of deportation of foreign-born residents convicted of a wide range of crimes. This enhanced deportation policy vastly increased the number of gang members being sent home to El Salvador, Honduras, Guatemala, and elsewhere.

According to one estimate, 20,000 criminals returned to Central America between 2000 and 2004. That trend continues US immigration authorities removed nearly 6,000 suspected gang members in 2018 alone – around 1,300 of them from the MS13.

Central American governments, some of the poorest and most ineffective in the Western Hemisphere, were not capable of dealing with the criminal influx, nor were they properly forewarned by US authorities.

The convicts, who often had only the scarcest connection to their countries of birth, had little chance of integrating into legitimate society, and they often turned to gang life. In this way, the decision to use immigration policy as an anti-gang tool helped spawn the virulent growth of the gang in Honduras, El Salvador and Guatemala.

The MS13’s principal activities vary a great deal from one region to another. In Central America, where the gang’s reach and size (relative to overall proportions) is largest, the MS13’s operations are more diversified. This includes extortion and controlling the neighborhood petty drug market.

Their crimes, such as extorting bus companies, are arguably more disruptive on a daily basis to more people than any other criminal activity in the region. In the United States, the MS13 focuses on local drug sales and “protecting” urban turf to extort small businesses and underground bars.

There is some evidence the gang is involved in other, more sophisticated transnational criminal activities, most notably international drug and human trafficking rings. But the gang’s role in these activities appears to be largely in a support rather than a leading role.

What’s more, in the more than a dozen international drug trafficking cases tracked by InSight Crime, the gang members worked with networks outside of the MS13 structure, most notably the Mexican Mafia’s networks. In all instances, the drug trafficking was in very small quantities compared to other international criminal groups.

Throughout its existence, various governments’ attempts to reduce the threat posed by the MS13 have instead often had the perverse impact of spreading the threat posed by the gang. Perhaps the most obvious example is the aforementioned policy of deporting foreign nationals committed of crimes in the United States.

But Central American governments have also contributed: the “mano dura,” or “iron fist” policies, which jailed youths based on appearance and association as well criminal activities, became the norm following their implementation by Salvadoran President Francisco Flores in the late 90s. As a result, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala saw their prison populations overflow with members of the MS13 and other gangs.

Because the brittle prison systems in each of those nations was unprepared for the sudden influx of thousands of violent and organized gang members, violence rose sharply inside jails. In response, authorities separated the gangs, but this opened up space for them to reorganize.

In prison, for example, they are given a freedom and safety that is no longer possible on the outside. They frequently have access to cellular phones, computers and television. As a result, the MS13’s Central American branches have been able to rebuild their organizational structures from inside prisons walls, as well as expand their capacity to carry out crimes such as car theft, extortion and petty drug dealing.

The gang is now in its second generation, and the cycle appears difficult to break. Youth enter as they often see it as their only way through the rising violence around them. Entry is often equally violent, sometimes including a “13-second” beatdown.

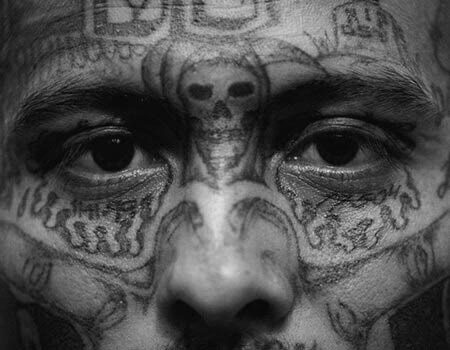

Older members seeking to break free find internal rules they might have created keeping many of them from separating. The gang, for example, penalizes desertion with a death sentence. Even if they can break free of their membership, their tattoos have often branded them for life.

In El Salvador, at least, MS13 members saw something of a reprieve from their usual violent lifestyle since their leaders and their Barrio 18 rivals agreed to a nationwide “truce” brokered through community groups and the Church and facilitated by the government in March 2012. The apparent ceasefire was followed by a tremendous drop in El Salvador’s homicide rate that many hoped would signal a major shift in citizen security in the country.

However, some critics of the truce feared it dangerously heightened the profile of the street gangs, and provided them with the resources necessary to exert greater influence on government institutions. The United States was also reluctant to endorse the gang truce, increasing pressure on the MS13 since its implementation.

In addition to designating the gang as a transnational criminal organization in fall 2012, the United States imposed economic sanctions on six MS13 leaders by adding them to its Specially Designated Nationals List in June 2013.

Concerns over the truce were further fueled by reports of rising extortion and disappearances during the truce period, as well as the discovery of mass graves. Additionally, homicides began rising again in mid-2013 as the truce unraveled, and continued to rise throughout 2014 and early 2015.

By 2016 and in the midst of record levels of violence, the government launched a series of “extraordinary measures” to aggressively crack down on the MS13 and the country’s other gangs.

The MS13 soon found itself locked in what resembles a low-intensity war with government security forces, with the gangs sustaining the bulk of casualties. The gang has also had to deal with the emergence of anti-gang death squads composed largely of members of the military and police.

Violence has since cooled significantly, with homicides plummeting to historic lows in 2019 and 2020 amid allegations of a renewed entente between the MS13 and the El Salvador government. Multiple state officials told InSight Crime there is an informal pact between parts of the government and the gangs, which broadly speaking sees the gangs lower the murder rate in exchange for better prison conditions.

Evidence of the alleged pact had surfaced largely thanks to local press, with the El Faro media group publishing prison logs, surveillance photographs, intercepted phone calls and other materials documenting a series of meetings between top state officials and leaders of the MS13. However, the El Salvador government has repeatedly denied the existence of any gang pact.

The MS13 also boosted its political capital in El Salvador following the onset of the coronavirus pandemic, in early 2020, reportedly leveraging its vast territorial control and prior relationship with the state to impose curfews, enforce mask-mandates, and run government-financed relief programs in cash-strapped communities where the government has minimal presence.

The gang’s domestic exploits may also have helped weather persistent pressure from US prosecutors, who in 2020 began targeting top MS13 leaders in El Salvador with terrorism charges and requesting extraditions. With the extraditions having largely been blocked by El Salvador’s Supreme Court, there has been speculation as to whether MS13 members are being protected as part of the alleged unofficial pact with the government.

Leadership

On paper, the MS13 has a hierarchy, a language, and a code of conduct. In reality, the gang is loosely organized, with cells across Central America, Mexico and the United States, but without any single recognized leader.

The leaders are known as “corredores,” or “runners,” and “palabreros,” loosely translated as “those who have the word.” These leaders control what are known as “cliques,” the cells that operate in specific territories.

These cliques have their own leaders and hierarchies. Most cliques have a “primera palabra” and “segunda palabra,” in reference to first and second-in-command. Some cliques are transnational; some fight with others and have more violent reputations. Some cliques control smaller cliques in a given region. They also have treasurers and other small functionary positions.

The MS13 also has programs, under which it groups numerous cliques. At its most potent, the MS13 leadership can control the actions of these cliques from afar. This fluid, diffuse structure makes the gang resistant to any single government’s attempt to crack down on it. Arrest the “primera palabra” and the “segunda” quickly assumes control.

Geography

Numbers vary, but the US Southern Command says there are as many as 70,000 gang members in the Northern Triangle. The proliferation of gangs has accompanied a rise in murder rates.

Of these gangs, the MS13 is the largest in the region. Central American immigration to other parts of the United States, such as New York City and the Washington, DC area, helped foster the spread of the MS13 within the United States as well. The gang has also begun to appear in parts of Europe, most notably Spain and Italy.

Allies and Enemies

The MS13 is enemies with the Barrio 18, another street gang with an extensive presence in Central America, Mexico and the United States. In recent years, the gang has sought to expand its political connections.

Video evidence surfaced in 2016 showing that the gang had secretly negotiated with leaders of El Salvador’s governing party, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (Frente Farabundo Martí para la Liberación Nacional – FMLN), offering them political support in exchange for economic benefits.

Prospects

The long-term effects of the gang truce in El Salvador continue to unfold, but it appears the MS13 is as strong as ever, and will remain an immense source of citizen insecurity and a potent force.