In this run-down neighborhood in Guatemala City, the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) does not exist. And yet, there are still a host of emeeses, as the gang’s members are known.

One of the walls at the entrance to the community is emblazoned with graffiti claiming the presence of a gang and a specific clique, “Mara Salvatrucha 13 – Tiny Locos.” In a corner at the end of the wall, a boy wearing tall socks and a pair of knock-off Nike Cortez sneakers, the gang’s trademark shoe, scowled at me as he spoke through his headphones – likely announcing my arrival.

*This article is part of a four-part investigation, “MS13 & Co.,” diving into how the MS13 grew from humble beginnings to become a business powerhouse with investments in numerous businesses, both legal and illegal, across the Northern Triangle. Read the complete investigation here or download the full PDF.

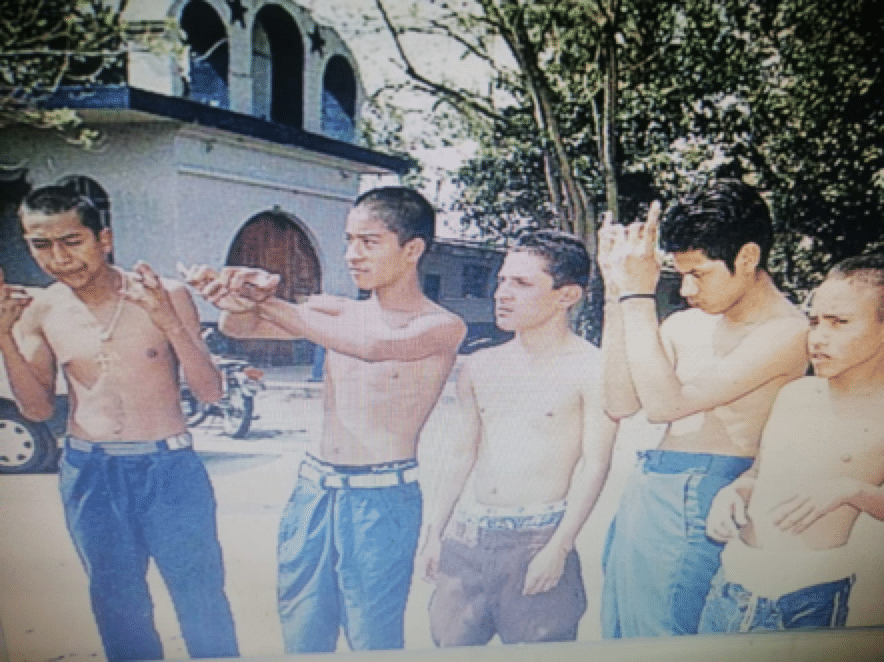

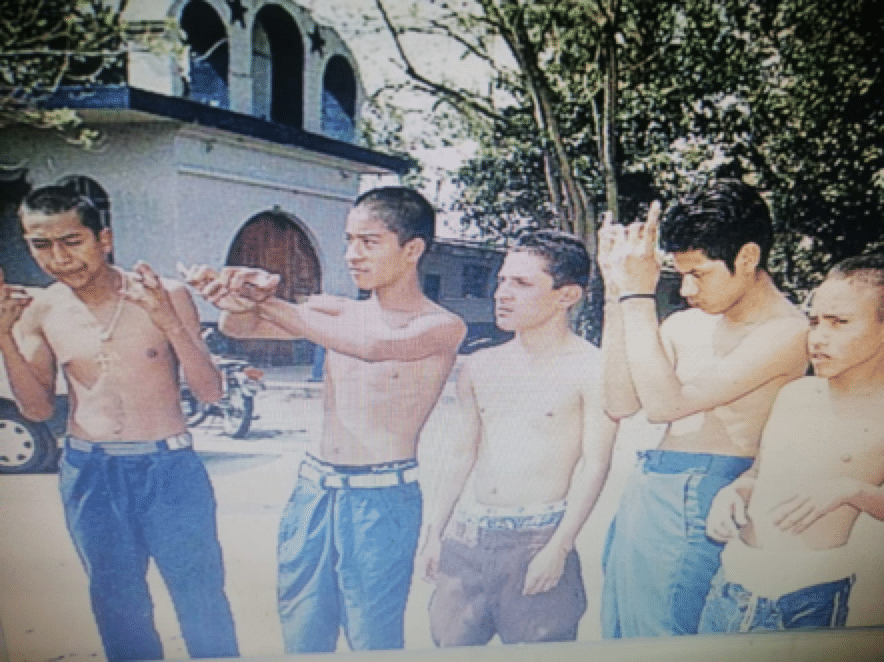

I guessed correctly. Three more boys were waiting for me on the next block. They watched me pass by with scathing eyes and informed the others. The further I ventured into the neighborhood, the more visible the MS13’s presence became. If the first guy had imitation shoes, those in the next alley wore originals. Those standing in the following pathway have tattoos and, even though it is cold, they take off their shirts to flaunt them

But despite the undeniable presence of the MS13’s members, all of my sources agreed that the MS13 does not officially exist here.

Caballo Loco (Crazy Horse), the most veteran emeese in the neighborhood, guided me through the alleys and pointed out the gang members, their graffiti and their hideouts.

He is protected by slum rules, those that grant veteran bandits a godlike status. The seasoned gang member recounts each of the street corner’s bloody tales and explains, with tremendous patience, the logic that allows dozens of neighborhoods in the Guatemalan capital to be filled with gang members even though they don’t belong to the MS13.

The MS13’s Beginnings in Guatemala

I met Amable after some poor directions led me to go around in circles near Guatemala City’s cathedral one day in April 2021. Amable no longer looked or spoke like a gang member. He had long ditched the baggy clothes, the Nike Cortez and the killer’s stare.

Amable now wore tailored pants and leather shoes. He had a job, and the two letters he once proudly displayed on his torso – “M” and “S” – were hidden behind his button-down shirt. He was accompanied by Furiosa, a grey pitbull with a huge metal chain around its neck. In contrast to her companion, Furiosa definitely had the look of a murderer, but Amable swore it has never attacked anyone, at least without a motive.

“She’s calm. The chain is just so people don’t get nervous,” says Amable, counting on Furiosa’s good manners.

Amable used to be a member of the MS13. In some ways, he still was. His skin still bore the gang’s two letters, and although not linked to any active clique, he said that he still carried the neighborhood in his heart. He said he still felt that he belonged to the group that served as his family for so long.

The story that binds Amable to the MS13 began in the early 1980s in Guatemala City. He was just a few months old when he had his first respiratory crisis. For the next four years, Amable’s breathing difficulties left him with severe asthma. He recovered but eventually suffered a bout of pneumonia, which ravaged his already weak lungs.

His mother, overwhelmed by her son’s increasingly frequent and aggressive illnesses, decided to leave the occasionally chilly Guatemalan capital. They moved to El Salvador, to the city of Sonsonate, on the country’s Pacific coast. She thought that the heat and humidity of the Pacific would help her son’s lungs to heal. She was right, but then poverty struck.

His mother never studied. She supported her family by making piñatas. From the time he could remember until he was 12 years old, Amable sat next to his mother as she twisted wire and assembled the piñatas so he could buy food.

That lasted until the early 1990s, when his mother became ill. A case of appendicitis was missed by a doctor, turned into peritonitis and she was bedridden for months. Amable had to assemble the piñatas on his own. But they weren’t as pretty as the ones his mother made, so almost no one bought them.

Over time, with food money running low, Amable mastered how to steal food, often from big birthday parties and weddings. He also learned how to trick supermarket cashiers so he could shoplift with impunity.

It was around that time that he stumbled upon the MS13.

“The first one who reached out was a friend’s brother. ‘La Mara Salvatrucha,’ he yelled. – ‘La Mara Salvatrucha’– I responded, without really knowing what it meant. From that moment on, no-one could peel me away from them,” Amable said, laughing.

In 1994, life for the MS13 in Sonsonate was violent but fun. The Salvadoran civil war had ended and gang members deported from California were recruiting poor children and adolescents from the city’s neighborhoods. Life was about dancing, getting high, stealing and chasing girls. If any member of the Barrio 18 – the MS13’s arch-rivals – showed up, half-hearted fights with bats and chains might break out.

But this state of affairs didn’t last long. Bullets began to fly and blood began to flow. The MS13’s first cliques in El Salvador were quickly established and led to many conflicts and rivalries. The dynamic no longer worked for Amable. For him, the MS13 had always been more about parties than funerals. He returned to Guatemala alone, a country he had not forgotten but had never really got to know.

MS13 Profile

The Yin Yang Gang

In the early 1990s, California-born gangs like the MS13 adapted to life in Central America. They recruited almost anyone who wanted to join, according to Amable and numerous veteran gang members who spoke to InSight Crime but asked to remain anonymous.

“The 1990s were the golden years for the gangs,” said Amable.

The gang was a family, albeit a dysfunctional one, with no parens but with hundreds of brothers. The deported gang members that landed in Guatemala taught their new friends about clothes, secret codewords and sneaker brands. They were told what words they could use and what colors were correct, but received little training in carrying out violence. It wasn’t imperative.

At the time, the MS13 and Barrio 18’s interactions were governed by an old gang truce, settled in Los Angeles, California. It was a truce by which the gangs coexisted, communicated, grouped against common enemies and fought one another with honor. One on one, machete against bat, knife against chain. This street pact was known as “El Sur” (The South). And El Sur was, in the 1990s, the law of the land in the Guatemalan capital and surroundings.

In 1995, after moving back to Guatemala City, Amable wandered the city streets looking for his family: the MS13. He found some graffiti, heard some rumors, but months passed and he was still alone. He gathered food as he could, stole some clothes and begged for money at traffic lights. His family was nowhere to be found.

One Saturday, as he wandered around the city, Amable wound up at a street party near a small hill in downtown Guatemala City known as “Cerrito del Carmen,” adorned with a church and surrounded by working-class communities.

That day, the community was celebrating the Virgin Mary, with locals dancing cumbia and drinking cheap liquor. Between drinks, some boys told Amable about a nearby alley where gang members used to meet up. He could not wait to find out more.

“I was crazy about it. I only thought about the MS. It was already in my heart,” Amable told me on one unusually cold afternoon, while eating pizza in a small restaurant in Guatemala City’s Historic Center.

When Amable found the alley in question, he stumbled upon a group of gang members. “Go to the Barrio 18, you son of a bitch,” they yelled at him. As street rules dictate, Amable did not back down: “The Mara Salvatrucha, you stupid sons of bitches,” he replied. Since coming back to Guatemala, this was his first opportunity, and perhaps his last, to defend the gang so entrenched in his heart.

But instead of beating him up, the gang members patted him on the back. Amable’s apparent rivals were actually members of the MS13 setting a trap for dieciocheros, as Barrio 18 members are known. It was also a test for emeeses, one which Amable passed with flying colors. From that day on, he was no longer left alone to wander the streets of Guatemala City like a lost animal. He had found his family.

Back then, Amable’s group didn’t get up to much. The MS13 was little more than a rumor in the city’s slums. They lived in the “Yin Yang House,” an abandoned building in front of Cerrito del Carmen. Engraved in cement at the building’s entrance was the Yin Yang symbol, the oriental sign representing duality. The previous owners most likely thought it was elegant, or whoever built the building perhaps liked it and decided to put it there. In any case, the symbol inspired limitless stories and legends among the young gang members. They felt incredibly special for living in such a cool house.

It was there that these first emeeses threw parties, invited over girls and took drugs until they passed out. Bloody episodes were few and far between. Amable could only recall two: the time that Casco, a Honduran MS13 member who arrived in Guatemala in search of adventure, blew his brains out playing Russian roulette. The second occurred months later when Security, from the same gang, blew his head off playing exactly the same game, with the same gun, in the same house.

At the time, those were the only bodies the young gang members had to dispose of. Other local gangs were not a threat. The El Sur non-aggression pact protected the party lifestyle.

By 1996, Amable had become a small-time gang leader, leading a couple of dozen homeless boys. They took control of Cerrito del Carmen and the surrounding area.

But Amable and his friends lived like Peter Pan and the Lost Boys: as if they would never grow up.

A Virus Infects El Sur

That same year, in 1996, when Amable and dozens of boys from Cerrito del Carmen were fooling around as gangsters, a surly child entered the juvenile detention center in San José Pinula, on the outskirts of Guatemala City. He seemed angry at the world and everyone around him. His name was David Ixcol.

The boy came from one of the roughest slums in the dense urban sprawl surrounding Guatemala City: Ciudad del Sol. He belonged to one of the first MS13 cliques in the country, the Coronados Locos Salvatrucha. He arrived at the detention center having just dethroned the clique’s leader, Huevo Loco (Crazy Egg). This was no mean feat. Huevo Loco was violent and aggressive, his face scarred by an old bullet wound. And Ciudad del Sol was no place for the weak. The El Sur pact had little influence there. The slum was also home to the so-called CDS, a contraband network specialized in mugging and smuggling, as well as older gangs like the Breikeros, united by their love of hip-hop and breakdancing.

In no time at all, David Ixcol would make a name for himself as El Soldado (Soldier) of the Coronados clique. Days after entering the detention center, he fashioned a shiv and waited for nightfall. Ignoring the non-aggression pact between the gangs, Ixcol grabbed a Barrio 18 member in his sleep, took out the shiv and brutally drew an X across his neck and chest, defacing the number 18 tattooed on his torso.

Rattled by the incident, the different gang leaders held a meeting for fear that the much-loved pact could be ruined. Soldier defended himself, arguing that if the victim had been a true gang member, he would never have allowed himself to be attacked that way. When pressed further, Soldier shrugged off the accusations and said he had no interest in explaining himself to people who preferred talking to fighting.

It was that day – although nobody knew it at the time – that Soldier from the Coronados broke the El Sur pact. For a while, the cracks could be papered over and the party lifestyle could continue, but soon, the gangs would be brutally forced to accept that era had come to an end.

Soldier served a short sentence but was back in the same detention center the following year, in 1997. He was facing more serious charges this time but had an improved entourage. He entered the center in San José Pinula with a handful of emeeses that still lead the MS13 today: El Brown, El Mamut, El Psico, and the youngest of all: Célbin.

Soldier and his friends asked to be transferred to a larger facility, known as Gaviotas. In there, minors and adults were mixed in together, and there was a well-established nucleus of MS13 members. The director in San José Pinula transferred them with pleasure, happy to pass on his problems to someone else. The only one left behind was Célbin.

Other gang members detained at the time told InSight Crime of the furious tantrum Célbin threw when he was told the news. He was too young and too small to be housed in Gaviotas, where he would likely be mistreated and abused.

Celbín was left alone, bitter and grumbling, a skinny boy of 13 or 14 years of age. He had grown up on the streets of Ciudad del Sol and was raised by the MS13 from a young age. But that day, Célbin was left without his family.

Soldado and his friends soon established themselves as the leaders of Gaviotas, both for the MS13 and other imprisoned gang members. Soldier made a name for himself and was backed by most of the detainees, regardless of their gang allegiances. And it didn’t take long for the MS13, though a scattered and disjointed gang, to call Soldier its leader.

Back in San José Pinula, Célbin had also carved out a small kingdom for himself in the juvenile detention center. But just like his mentor, Soldier, Célbin never saw the benefits of El Sur. It was an obstacle that prevented him from reaching his enemies. The pact was a burden for Celbín and he would soon remove it, but not before using it to his advantage.

MS13 in the Americas: Major Findings

In 1996, not all gang members lived in the never-never land of El Sur.

Caballo Loco grew up in one of the least hospitable parts of Guatemala City, where many lived from what others threw away. They sorted the garbage, stacked it, hoarded it and sold it. Sometimes, they used it or even ate it.

When he was 12, Caballo Loco created a small gang with his friend Julián. Neither was in school and their job was to sift through the trash, looking for anything valuable. They were partial to a bit of theft and would fight with anyone up for a scuffle. Later, their crew was joined by two other boys, but the worst they got up to was stealing trash or breaking lampposts. Until the MS13 arrived.

The first emeese to arrive in the neighborhood was known as Skiny, a Salvadoran gang member deported from the United States and a member of the so-called Normandie clique of the MS13. He told the boys about the wonders of gang life, about how they could finally find a home, a meaning, an identity. He said they could ditch the half-life they were living now and truly begin to exist.

He was offering a fresh start. But the problem was he never told them how to get started. Rather, Skiny left the neighborhood, and they never saw him again.

The boys did have a few ideas about how to get going, and Skiny had told stories about his own initiation. The rest was up to their imagination.

So, on one morning in June 1996, the four boys from the garbage dump formed a circle and flung themselves at one another, the idea being to fight it out and decide on a leader. The melee ended when Perro Loco went down, leaving his friend Julián as the last man standing. With their leader defined, they all chose a new alias and the clique was born.

It was baptized the Tinys Locos Salvatrucha, a reference to the founding members – all children – and their parent organization, the Mara Salvatrucha 13. The gangs take your weakness and turn it into a strength. Or, at the very least, you end up with a cool nickname.

A Leader Emerges

The gangs have a novel way of naming new members. You take something used to embarrass them and turn it into a strength. Someone with an ugly face might become El Engendero (The Freak). Someone shy or reserved could be named Serio (Serious).

Célbin, the boy who cried when he was separated from Soldado de Coronado and the other gang members from Ciudad del Sol, had grown up on the street. He was thus named El Vago (the Drifter), of the Coronados Locos Salvatrucha clique.

Soldado de Coronado, who had infamously defaced the tattoo of a jailed Barrio 18 member with his knife, retired from the gang in the late 1990s. He was a fleeting leader, a violent but short-lasting blaze. Vago was different. He became a leader not only for the emeeses detained in the Pavoncito prison near Guatemala City, but also for all of the gang members imprisoned at the jail. He organized secret meetings at night and coordinated with gang members on the outside to amass a small arsenal.

Vago organized a prison riot on December 23, 2002. He and his fellow gang members launched an attack on the prison’s de facto leaders, mostly long-time criminals with connections to Guatemalan military elites and who had access to firearms inside the jail.

Indeed, from the early 1990s up until that day in 2002, gang members had been outcasts in the country’s prison system. They were the lowest of the low in the criminal underworld – conflictive, rowdy, and rebellious. They committed crimes, but not ones that made them any real money. And after a decade of enduring rape, torture, beatings and robberies behind prison walls, they were ready to rise up and take on their abusers.

The December 2002 uprising lasted 24 hours. Fourteen bodies, those of the prison capos and their henchmen, were riddled with bullets and machete wounds. Vago, aside from leading the rebellion, had also beheaded Julio Cesar Beteta, the prison’s top boss and the cousin of a well-known military official. He grabbed Beteta’s head by the hair and paraded it in front of dozens of journalists gathered outside the prison. One of those in attendance, who asked not to be named, told InSight Crime that Vago spent at least an hour carrying the head around.

It was then that Vago decided to change his name. He ceased to be Vago and was reborn as Diabólico. Back then, he was a respected leader within the gang. But ever since that day in 2002, he has been the one steering the MS13 ship in Guatemala.

Farewell to El Sur

On August 15, 2005, the MS13 tore up the pact of El Sur. It all went down in a jail in Escuintla, 60 kilometers south of Guatemala City, where dozens of emeeses attacked their Barrio 18 counterparts with bullets and machetes. [LINK]

It was an ambush, a betrayal. The army of gang members that had banded together to defeat the Pavoncito prison bosses just three years ago, was dissolved by the MS13’s bullets.

Unsurprisingly, the attack was organized and led by Diabólico.

The Escuintla riot was followed by three more in other prisons. Even juvenile detention centers played host to the bloodshed. The lust for war had penetrated Guatemala’s gangs ever since that boy from Ciudad del Sol slit the tattooed chest of a sleeping Barrio 18 detainee. At the time, the gangs ignored him and continued to honor the pact. This time, that was no longer an option.

El Sur was dead and, with its demise, a whole new way of life came to the slums.

The MS13, under Diabólico’s command, closed its ranks. They no longer wanted to expand. Whoever wanted to leave was allowed to do so. One of those deserters was Amable.

He left the gang when it stopped being fun. On one occasion, in prison, MS13 members close to Diabólico held a trial for him. One of the charges against Amable was that he had previously been good friends with a member of the Barrio 18. Amable defended himself, saying his behavior was in line with the rules at that time, established by El Sur. The MS13 branded him a coward and threatened to kill him. Enough was enough for Amable, who was always more interested in parties than funerals – especially with his own funeral on the horizon.

“Do you miss your gang?” I asked Amable, years later, in downtown Guatemala City.

“I miss the gang I knew, yes. Those were good times. Now everything is screwed up. Everything is money. It is not like before. There’s no brotherhood among gangsters anymore.”

“If you could go back to those times, would you?”

“Yes, I actually would. But now the gang is tainted with a lust for money.”

Amable spoke earnestly while we talked outside an old building that once housed the first MS13 members in the city. Following Amable’s gaze, I spotted an old symbol, a piece of graffiti, almost worn away by storms, paint and the passage of time. It was the symbol of yin yang.

The era of party gangs ended in August 2005. It was a way of life that appealed to many Guatemalan children and teenagers left over from the armed conflict. They came to Guatemala City fleeing war and poverty and found themselves lost in a strange place, many without family. That era, when gangs were a haven, lasted less than ten years.

Then came the money. The times of easy-going gangsters like Amable faded away, like an old tattoo, like graffiti in the rain.

A Band of Professionals

“The MS13’s structure is much smaller than the Barrio 18, but it’s much more organized. They’re smarter. They try not to appear weak and to avoid appearing like gang members at all,” a former Guatemalan police officer told me in May 2021. “They have people studying law, business administration. They’re a mafia.”

The former officer spent five years pursuing the MS13, or trying to. After so long chasing the gang, he has a touch of admiration for them.

“They’re not like the Barrio 18. They have a leadership circle made up of nine people, all of them in jail. They divide their territory into three sectors of Guatemala City. There are as many as eight cliques in each sector, and all of them report to the head of that zone. That person then reports to the nine leaders in jail,” the former officer said.

“Leading the group of nine is a gang member from Ciudad del Sol: Jorge Yahír De León Hernández. He’s been the leader for more than a decade,” said the former officer.

Jorge Yahír is none other than Célbin. He later became Vago and finally Diabólico. That skinny kid throwing a tantrum is the one that went on to change the direction of Guatemala’s gangs.

The former police officer said that the MS13 was an enigma for authorities for many years. Just when investigators thought they’d found a line of investigation to pursue, the gang would murder the prosecutor assigned to the case. If the police found a key witness within the gang, they would disappear without a trace. Authorities could spend months without hearing anything or arresting any gang members. Then, all of a sudden, the gang would crop up again under the noses of the police.

“In my opinion, the way they extort is different to the Barrio 18. [Barrio 18 gang members] just come and ask for money and say that if you don’t pay, they’ll kill you. But these guys [MS13 gang members] sell protection. I had to investigate a case like this, involving sweet vendors on the Chimaltenango [bus] route,” the former cop said.

He was talking about July 2017, when bus drivers on a route from downtown Guatemala City to Chimaltenango, a town 50 kilometers from the capital, complained to the MS13. Despite paying the exorbitant extortion fees demanded by the gang, other criminals kept preying on the route. The promised protection wasn’t working. Under the guise of selling candy or cigarettes, small-time punks would board the buses and assault the passengers. This called the MS13’s power into question, and, above all, their capacity to control the route. If they couldn’t protect the buses from these petty thieves, then why would the drivers keep paying them for protection?

At least 13 would-be extortionists died between July and August 2017, according to the former police officer and documents from the Attorney General’s Office obtained by InSight Crime. This time round, simply kidnapping and burying them in a far away field wasn’t enough. The MS13 wanted to showcase its power for all to see. Four were shot dead at a gas station on July 28 that year. Eight others were killed the next day, and one more on a road heading out of Guatemala City. On July 31, two more were murdered at a restaurant in El Tejar, a small town on the same bus route.

This particular bus route is long. And the deaths, scattered like bread crumbs along it, left a trail leading straight to the MS13. The former police officer knew it and tried to convince his superiors that this was a single case, rather than a series of unconnected crimes. But his efforts were in vain. The MS13 got away with it. The cases couldn’t be linked, and the gang returned to the shadows.

“The [MS13] keeps extorting. But they’ve evolved. Now, for example, they have businesses. Many of the [moto taxis] are theirs. Many of the used cars sold in Zone 13 are also theirs. A number of corner spots used to deal drugs are theirs too. But they are counting on going unnoticed,” said the former cop.

He added the gang succeeds in operating in the shadows because there aren’t that many of them.

“Each clique has between four and eight members, no more. They are what they are. They don’t accept anyone else,” said the cop.

According to the former police officer and 35 other people interviewed in five focus groups in the Guatemalan capital, the MS13 has diversified its ways of making money. The gang no longer depends on extortion as its main source of income and has instead started setting up its own businesses.

Over time, extortion has skyrocketed in Guatemala, according to data from the Attorney General’s Office. In 2004, with the MS13 under Diabólico’s control, authorities registered just 738 extortion complaints. That figure rose to 9,430 complaints in 2010, before hitting 15,495 by 2019. 2020 saw a sharp decline, with just 13,116 complaints, possibly a result of the lockdowns brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Extortion bounced back in the first five months of 2021, with a reported 11 percent increase in complaints compared to the same period in 2020. But the data doesn’t tell the whole story. According to several sources in the police and Attorney General’s Office, most extortion crimes go unreported.

Today, a decent chunk of extortion threats are made by “imitators,” or so-called “copycats,” who pose as members of the MS13 or Barrio 18 despite not being members, according to Guatemalan authorities.

When asked about the parameters that define whether or not someone is a gang member or a copycat, sources within the Attorney General’s Office said it’s quite clear in the case of the MS13. If they’re under Diabólico’s command, they’re MS13. If not, they’re a copycat.

The Possum Strategy

August 15, 2017, marked the 12th anniversary of the massacre that tore apart El Sur. The MS13 and the Barrio 18 tend to commemorate this day in typical street-gang fashion: with gunshots.

The former police officer knew this and alerted his colleagues. But August 15 came and nothing happened.

As it transpired, a truck transporting an MS13 prisoner from a prison in southern Guatemala to a hospital in the capital was delayed for bureaucratic reasons, and made the journey on August 16 instead of the previous day. The convict, Anderson Cabrera Cifuentes, was a member of the Vatos Locos clique and had been sentenced to over 100 years in prison for extortion and a string of murders. According to sources in the Attorney General’s Office, this included the 2010 murder of a police investigator and the killing of five shopkeepers who refused to pay extortion fees.

That day, an MS13 commando attacked the hospital, murdering two correctional officers that accompanied Cabrera Cifuentes and two hospital security guards, as well as two teenagers and one other individual. On fleeing the scene, the attackers took Cabrera Cifuentes with them.

The MS13 disappeared again.

This was the second-to-last major showing of the MS13 in Guatemala. The only subsequent time the gang has been in the spotlight came with the death of Cabrera Cifuentes on October 4, 2018. He decided to shoot himself in the head rather than returning to jail.

Since then, the MS13 has been a minor player when it comes to violence in Guatemala. Instead, the gang’s appearances have been largely enigmatic.

On December 22, 2019, Diabólico and his gang again emerged from the shadows. This time, he wasn’t parading around the head of any decapitated prison boss, nor was the gang accused of some audacious, bloody rescue. Instead, Diabólico welcomed a team of Spanish journalists to the Fraijanes II Prison in Guatemala City to talk up a dental clinic and t-shirt printing business the gang operates behind bars.

Other media outlets came to the prison after that interview. The majority of them came at Diabólico’s request. In these interviews, the leader – less skilled with words than a machete – put together a smooth pitch in which he presented – or at least tried to – the MS13 as an organization that fought to end extortion, like someone trying to kick a bad habit.

When interacting with journalists, Diabólico never fails to mention the MS13’s distaste for fighting. He consistently says he doesn’t want to be seen like the MS13 in El Salvador or Honduras: crammed into tiny prison cells and being killed by the police and military. He insists that they’re no longer a threat. Rather, if the government were to give them a chance, they would quit extortion and committing crimes altogether. They’d go back to being a group made up of working gang members.

In 2021, authorities transferred 194 MS13 members, including Diabólico and other leaders, from the Fraijanes II maximum-security prison to a prison with less restrictive measures: Pavoncito. The prison where everything began, where 19 years ago a group of lowly gang members rose up against the Guatemalan prison elites and put them to the sword. When El Sur was still alive.

Despite my best efforts, and unlike other journalists summoned by Diabólico, I did not manage to speak with the gang leader in person. On arriving at Pavoncito to meet him, in May 2021, his fellow gang members told me Diabólico was “tending to other matters.” They said it would not be possible to see him and that I should come back tomorrow.

The following day, a prison officer told me that Guatemalan authorities had blocked my entry to any jail in the country’s penitentiary system, instructing officials not to speak with me.

But I still managed to speak to Diabólico, albeit through other means. Part of the deal was not revealing how. During these exchanges, I asked the MS13 leader if he was planning on dissolving the gang. He replied with a slightly ambiguous “no.” Rather, he said he was trying to push the gang, step by step, towards giving up on crime and other acts of violence. He stressed there is no threat to the country, nor the government of President Alejandro Giammattei. He wasn’t trying to squeeze the government between a rock and a hard place. He knows that he can’t do that, not anymore at least.

Diabólico’s words sound more like a sly form of surrender than a threat. It’s normal. Nobody makes a threat without knowing they’re on the winning side. There are only 194 gang members in Pavoncito.

“They [the MS13] don’t number even 400 in jail, the majority have long sentences. In the streets they have 300 members at best,” a former organized crime prosecutor told InSight Crime.

He believes the MS13 has opted for what he calls the “possum strategy.” Move in silence, in the shadows, and play dead in the face of danger. And once the threat has passed, keep on going. As an evolutionary strategy, it’s not the most honorable or something that inspires tall tales. But one thing is certain. No hunter cares about having the head of a possum displayed on the wall.

The MS13: A Gang for All

One afternoon in May 2021, strolling through the same neighborhood where Caballo Loco founded a clique with his friends, the veteran gang member told me his group never really got off the ground. It never had the time to. Around 1999, just two years after they formed, they started fighting with another, stronger clique: the Normandie Locos Salvatrucha, one of the MS13’s largest and most notorious factions.

The war ended with two of the clique’s four founding members dead. In the aftermath, Diabólico banned anyone else from establishing an MS13 clique in the area. The kids from the trash heap had turned out to be very problematic. The MS13 was banned, but it is still very much present.

The MS13 is a brand. It doesn’t belong to anyone. Born in Los Angeles, California, the gang has grown, expanded, spread its wings and run free through the poorest neighborhoods of an entire region.

Even in Guatemala, where Diabólico is its undisputed leader, the MS13 brand has a life of its own.

Regardless of what Diabólico or the other eight MS13 leaders thought, gang members still stood guard on the neighborhood street corners in and around the city’s trash dump. Caballo Loco took me to the very bottom of the community, a place of narrow streets and mud. He showed me the alley where they came up with their own initiation ritual. He pointed out the precise spots where his friends – and enemies – were killed. He told me we should stop walking and not push our luck. We shouldn’t go where the neighborhood drug dealers sell little packets of marijuana and crack.

This is the MS13. A brand, not a transnational gang, despite what different government officials, police officers, the FBI, academics, journalists and former US President Donald Trump have all stubbornly insisted. The MS13 is within everyone’s, and that has allowed it to expand and survive.

The boys running the street corners in this community, with their little bags of marijuana and crack, who paint walls – and their own bodies – with the letters “M” and “S,” couldn’t care less if Diabólico recognized them as gang members. They’ll show their loyalty to the gang whenever they can.

And anyone receiving an extortion threat or being shot by a gang member doesn’t care if the orders came from Diabólico, the boy from Ciudad del Sol who tore apart El Sur.

*The detailed information offered in this article concerning the history of the MS13 and the personal lives of its members was compiled over several years through numerous interviews with gang members, former gang members, Attorney General’s Office and police officials, NGOs, activists, academics, as well as other sources close to the gang phenomenon.

*This is the third article in InSight Crime’s four-part investigation, “MS13 & Co.,” diving into how the MS13 grew from humble beginnings to become a business powerhouse with investments in numerous businesses, both legal and illegal, across the Northern Triangle. This chapter looks at a novel non-aggression pact between the MS13 and rival gang Barrio 18 that eventually unraveled amid bloodshed as ambitious MS13 members tried to stamp their authority on the gang. Read the complete investigation here.