On a sunny afternoon outside the blue facade of the Hotel Acapulco in the heart of Tijuana’s red-light district, several young girls walk the rough pavement, eyeballing a stranger, and muttering a series of incomprehensible one-word enticements. It’s a half-hearted attempt to get another client.

On the hotel’s ground floor, a seafood restaurant shares a wall with a motel named the Rapid Inn. Either residence can service this trade: For a half hour of sex work, these girls can make a meager 200 Mexican pesos (about $10).

*This article is the second in a three-part investigation, “The Geography of Human Trafficking on the US-Mexico Border,” analyzing how human trafficking networks operate along different parts of Mexico’s northern border with the United States. Download the full investigation here.

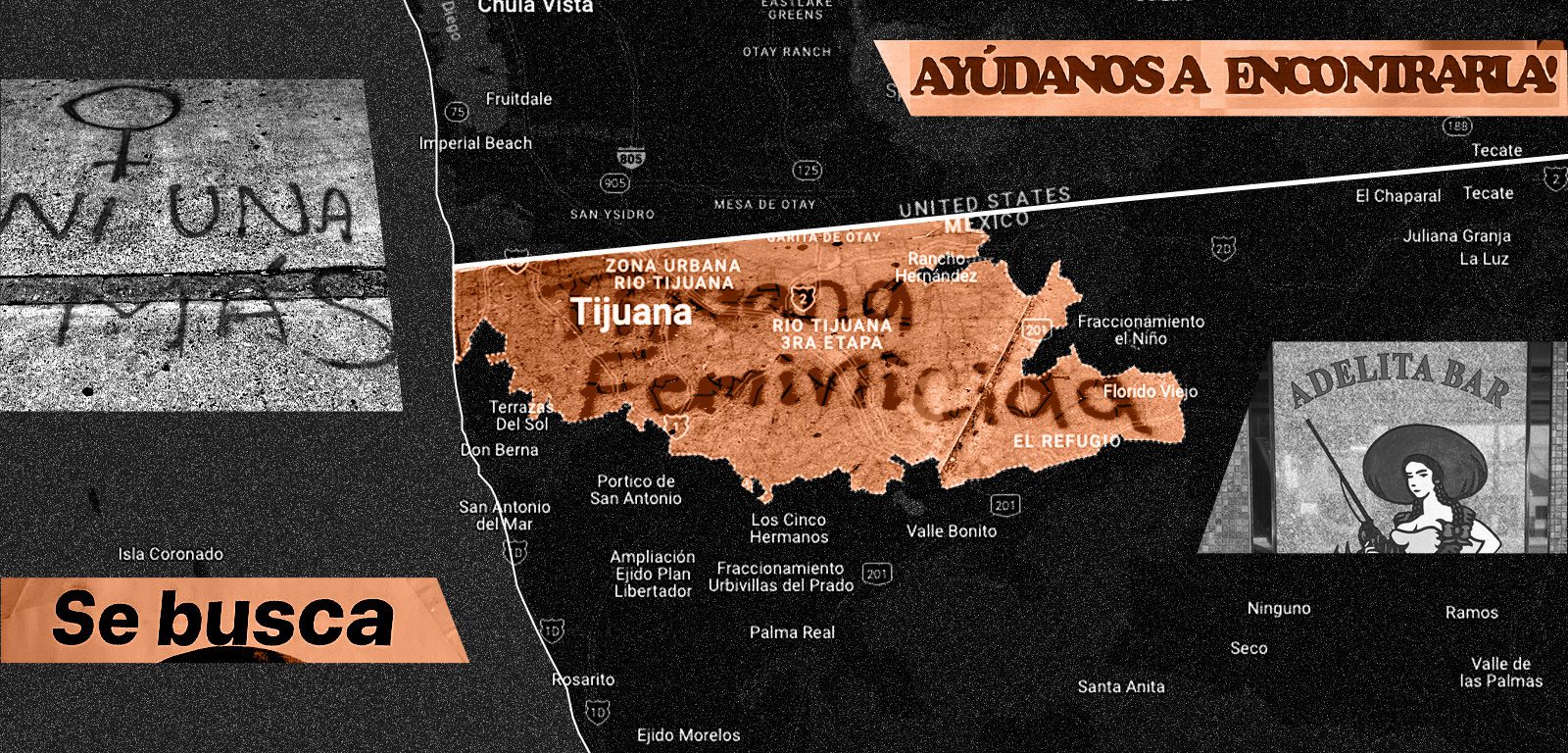

Located at the intersection of Coahuila and Constitution avenues between the offices of Tijuana’s transit and municipal police, these establishments form just one part of a vast network of sex work that is often infused with abuse, violence, and, in some cases, human trafficking.

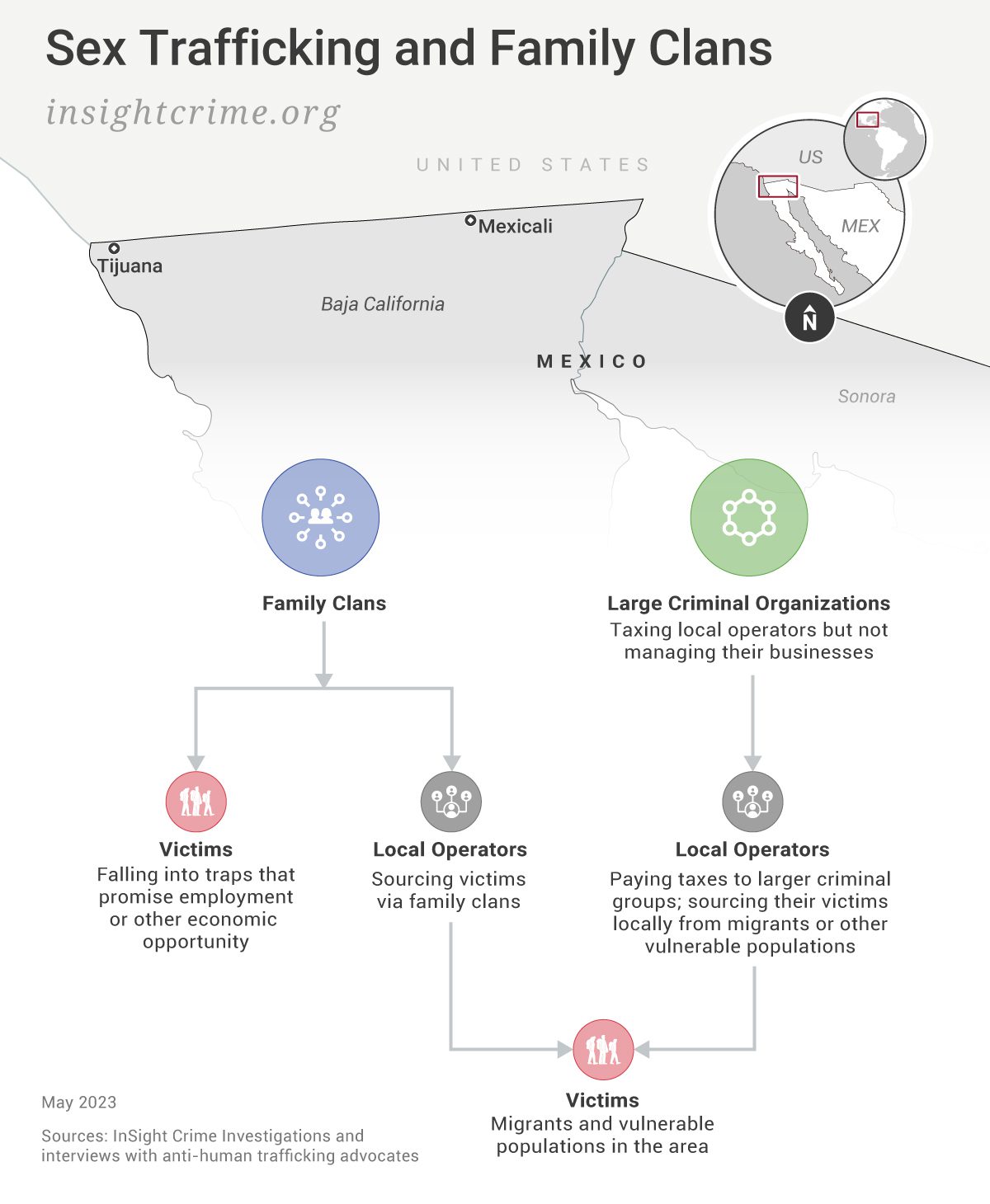

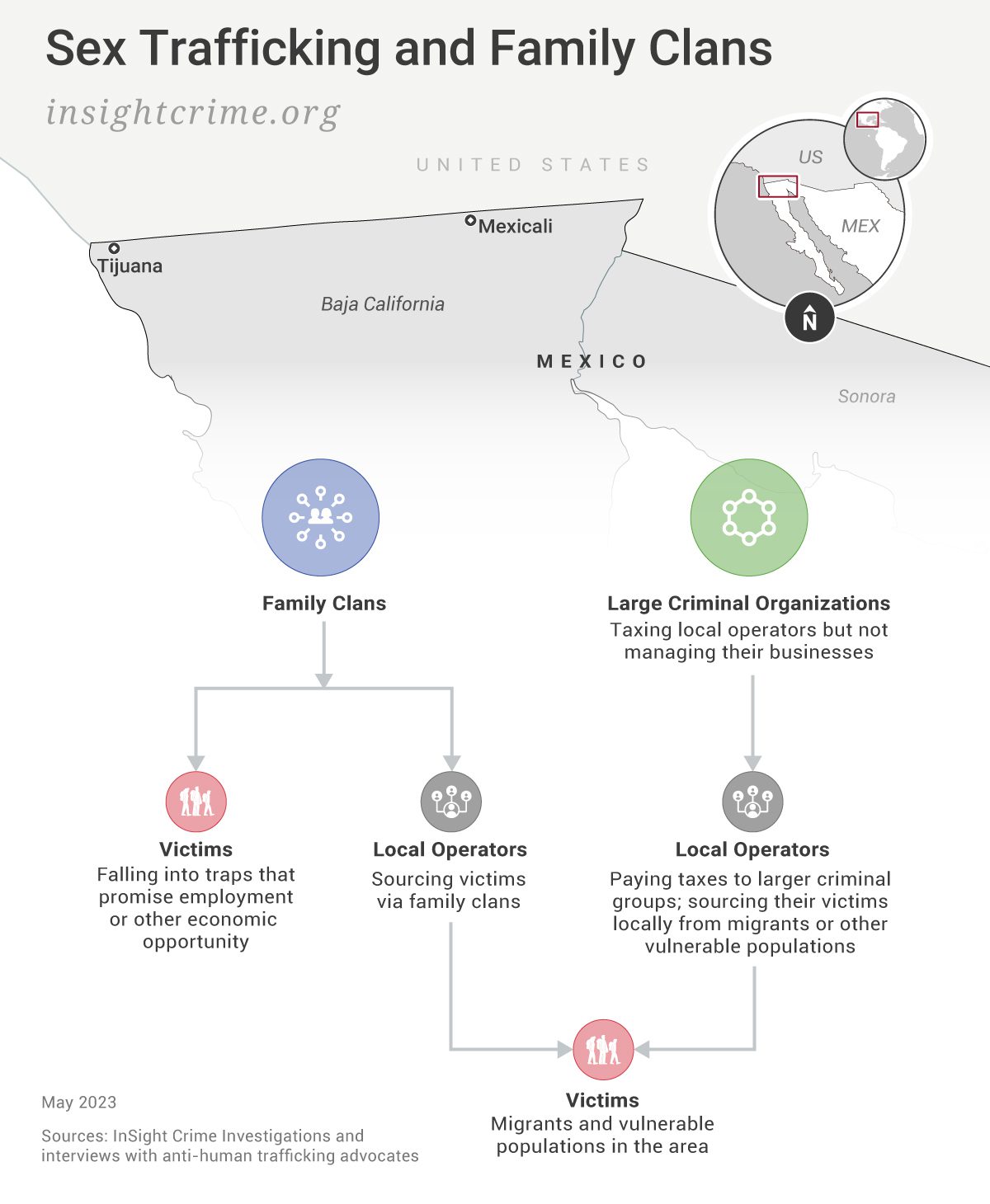

Tijuana, like many cities, appears to have a two-tiered system. On one tier are those on the streets approaching passersby. These women and girls are managed by padrotes, or pimps. These pimps often form part of small, family-based networks, which can also work with organized crime groups. They operate around the hotels, bars, strip clubs, food stalls, self-service stores, and barbershops that make up the red-light district.

A block away is tier two. There, three prominent gentleman’s clubs — Adelita Bar, Las Chavelas, and Hong Kong — have been mainstays for decades. Outside, several ATMs dispensing US dollars ensure patrons have enough cash to pay for a 20-minute encounter or extra services in a private suite.

The women working within these clubs have brokered agreements with the owners, according to various sex workers who spoke to InSight Crime on condition of anonymity. They exchange a portion of their earnings for protection from abusive and violent clients, as well as the right to stop working whenever they please. But it is common for club owners to break these agreements and force victims to continue working in abusive environments.

The underside of this business is also close. Along Revolution Avenue, one of the city’s main thoroughfares that cuts through a part of the red-light district, mothers of the disappeared hang up flyers of their loved ones. The flyers are filled with information and photographs of their beloved daughters, hoping for any help that could lead to a breakthrough. Some of the cases are years old.

A Monster at Home

Just before lunchtime at a small shelter on the outskirts of Tijuana, an American volunteer offered guitar lessons to a group of boys. The boys, who averaged about 11 years old, were victims of sexual abuse. Many had been exploited by their own families, as well as trafficking groups.

Indeed, it was at home where many of the victims’ problems began. Family members play a role in nearly half of child trafficking cases globally, according to data from the United Nations.

At the shelter, they are under the constant care of a team of dedicated staff and social workers, in part because child victims of sexual abuse flee their homes and are thus some of the most vulnerable to human trafficking. What form that trafficking takes varies, but shelter officials said it ranges from sex work to child pornography.

The shelter had two levels and a modest-sized garden. Initially, it served as public housing for workers within a government complex. Today, it has the capacity to accommodate up to a dozen children. The civil society group that has taken control of the shelter also operates another, slightly larger one for girls who have suffered abuse.

“It’s a serious problem [child sexual abuse], but we do what we can,” the volunteer, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of their work, told InSight Crime.

The shelter took form in the mid-2000s when the rising number of missing children in Tijuana caught the attention of a group of Christians who found themselves offering comfort and spiritual guidance to distraught mothers and fathers. Before long, they formed an organization. They called it No More Empty Rooms. Operating under the radar with limited public recognition, they have only recently sought media attention due to what they said is the escalating number of victims.

“This is the first time we have granted an interview,” said the group’s psychotherapist, who also requested anonymity for safety reasons. “There have been several situations in which we’ve been threatened directly.”

This comes as little surprise. The group’s members have frequently ventured into neighborhoods where even the police avoid patrolling to try and locate missing children. These areas are often hotbeds of violence.

Still, by blending in with religious services and operating soup kitchens in numerous neighborhoods on the outskirts of Tijuana, they have been quietly providing much-needed therapy and counseling. If they do not, the perpetrators of these crimes, often armed and hostile, harass the victims and their families.

The psychotherapist joined the group after struggling to answer a very basic question: Why are children disappearing? Before long, she said they “realized a very large monster exists here.”

But what did that monster look like and how did it operate? The answer to those questions has proven far more elusive.

Beyond the official crime statistics, there is little public information available regarding the trafficking of children. And while the state government’s Office for the Defense of Children (Procuraduría de la Defensa del Menor y la Familia) is filled with flyers of missing children, there is little official recognition or action to deal with the problem.

Thus, the group’s primary objective has become to rescue as many missing or captive children as possible, according to the psychotherapist. However, the monster, they have found, keeps producing more victims.

“In dealing with all of these victims, we have found a common thread: Since their childhood, they have experienced sexual abuse and exploitation within their own families or immediate environments,” the psychotherapist explained.

“Criminal networks do exist, but we have discovered that these networks often operate within the same family environment or the communities in which the victims live.”

Marginalized and Vulnerable

On the opposite end of Tijuana, shelters for members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bi-sexual, Transgender, Queer, or Intersex (LGBTQI+) community attempt to shield those it houses from the unbearable pressures they face outside. Most of their problems also began at home.

Stigmatized, abused, and ostracized, members of LGBTQI+ community are far more likely to leave their homes at a young age, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services. This puts them in extremely vulnerable positions.

On the streets, social rejection may be the least of their worries. What truly terrifies them is the relentless harassment from criminals, often facilitated by the inaction or active complicity of authorities and the participation of legal businesses such as nightclubs and hotels.

“In Mexico, merely being a person of sexual diversity means fighting for our survival,” said the director of one such shelter, who spoke to InSight Crime on condition we maintain their anonymity for security reasons.

For years, members of the LGBTQI+ community have suffered constant and pervasive discrimination that often goes unnoticed. Those who have been victimized by traffickers are further rendered invisible. The transgender community, in particular, is exploited for sex work and many other illegal activities.

“In some places, they are often recruited to work for organized crime groups as drug couriers or committing other crimes,” the director explained.

Others work in restaurants or bars, the director added. But due to a lack of formal opportunities, many also turn to sex work.

“They are coerced into these circumstances, and this connects them to trafficking networks and drug addiction,” said the shelter director, where 43 individuals sought refuge the day InSight Crime visited.

Many of them, the director said, were victims of exploitation. At times, the violence they confront turns deadly. But when a member of the LGBTQI+ community is killed, the director said, “nothing happens.”

The constant fear they feel is exacerbated by the level of impunity that surrounds the murders of transgender women. In recent years, two transgender women were killed in Tijuana. Both victims were in their mid-20s. One was tied up and set on fire in her own home. The other was stabbed multiple times. Authorities have not arrested any suspects in connection to the killings.

“If you are transgender, you are even more vulnerable than others,” said Jacqueline Aguilar, a transgender activist based in Ensenada, about 100 kilometers south of Tijuana. “If a [transgender] person manages to escape, it is hard to get authorities to pay attention. They often fail to recognize that a transgender person can be subjected to human trafficking. But it happens.”

Aguilar herself was pushed into sex work at the age of 13 as a means of survival. However, she escaped and became a leading activist for the rights of sex workers and transgender women after arriving in the port city in 2010.

The movement Aguilar leads has brought about significant changes. She said police officers no longer sexually abuse transgender women who engage in sex work and cases of extortion have dropped significantly. Nonetheless, the dangers persist. In November 2021, another activist, 22-year-old Alicia Díaz, had her throat slit in her own home.

Aguilar has witnessed the same criminal patterns in every victim she has encountered. Some are coerced into prostitution by their romantic partners in multiple cities, while others fall prey to criminal organizations.

“When these girls have the chance to escape, they take it. But when those who exploit them find out, they kill them,” she explained.

A Crime Transformed

It was 1992 when Victor Clark conducted his first interviews with sex workers and pimps in Tijuana. An anthropologist who later founded the Binational Center for Human Rights, he was one of the first to document sex trafficking in the city.

When he began, Clark chronicled how pimps relied on seduction and coercion to control multiple victims. For their part, the victims often struggled to view themselves as such — a common occurrence in this space due to the ways in which they are coerced and manipulated.

Three decades later, Clark sees a new generation of pimps. He says he began to notice it in the early 2000s. From family-based networks, they shifted, he explained from his office in Tijuana.

“It no longer consisted solely of brothers and cousins,” he said.

Clark pointed to an encounter he had with a pimp in Tijuana about 15 years ago who had introduced him to a Venezuelan woman.

“That’s when I began to realize they were hiring coyotes [human smugglers] to bring women from Central America,” he added. “It marked a transition towards a more complex organization akin to organized crime.”

The shift corresponded to other changes in Tijuana. As Clark explained, historically, the city was primarily an agricultural hub until the mid-20th century. But as urbanization took hold, people came to feed their vices for drugs, sex, and, during prohibition in the United States, alcohol. Crime and corruption took root.

After World War II, downtown Tijuana underwent a boom and expanded north towards the border with California. Housing developments were constructed to accommodate the migrants who flocked to the area looking for work, especially in the bars and cantinas. Pay-by-the-hour hotels also emerged, primarily to cater to those preparing to cross the border into the United States.

The square blocks around Coahuila and Constitution avenues soon became the focal point of the city’s sex trade and, as the criminal groups became more sophisticated, human trafficking.

Clark says this happens in broad daylight without any interference from the authorities.

“I have never seen [pimps] face any trouble or bribe anyone,” he said.

Prostitution is permitted in the red-light district, a designated “zona de tolerancia,” or tolerance zone, but not everyone does so voluntarily.

“There are countless padrotes out there,” he added. “I once asked them how many and they told me, ‘Director, there are so many of us, many towns are producing padrotes.”

When asked how many had been criminally charged and prosecuted in Tijuana, he sighed.

“Almost none.”

Similarly, no police investigations have established a direct link between child pornography and child prostitution and the children disappearing in Tijuana. But some individuals, such as Heriberto Garcia, the former ombudsman of Baja California, have persistently advocated for investigations into the sexual exploitation of children.

Garcia said this type of trafficking extends beyond family networks, particularly in a state like Baja California. It is part of one of the most powerful economic corridors in the world and home to a litany of organized crime groups.

“There is no business in which they [organized crime groups] don’t have a hand,” he told InSight Crime. “Anything can happen on the streets — people go missing for various reasons, including human trafficking, which I have no doubt is happening. Why has it escalated? Because of the prevailing impunity.”

A Crisis of Disappearances

There are many groups that are struggling to bring more attention to this problem. On March 8, 2022, for example, feminist collectives and families of missing girls and women marched through the streets of Tijuana and Mexicali. The gathering was just one of thousands around the world on that International Women’s Day.

But in places like Tijuana, it had a special urgency. As they progressed, they broke shop windows, spray-painted monuments and bus stops, and set fire to a municipal government building.

“Fuimos Todas,” they scrawled on the walls.

Roughly translated, it means, “We are all victims.”

Since 2015, Baja California’s state government has recorded more than 6,000 cases of disappeared women primarily under the age of 25. Other non-governmental groups like Elementa DDHH, a human rights organization based in Colombia and Mexico, have documented nearly 14,500 current cases of missing women and girls in Baja California, nearly half of whom are between the ages of 12 and 17.

Between 2007 and 2021, official data showed the disappearance rate in Baja California soared from just 15.5 per 100,000 people to around 76. The massive uptick in disappearances seen in recent years is strongly suspected to be linked to sexual exploitation and human trafficking, according to Gabriela Navarro, the technical secretary of the Inter-Institutional Commission Against Trafficking in Baja California.

“I believe sexual exploitation is involved in many of these [disappearance] cases,” she told InSight Crime. “Organized crime plays a role.”

Just what role, however, is harder to tell. Navarro pointed to her work on a number of cases to support her conclusions. In one case, she said, audio recordings reviewed by authorities revealed that one kidnapper was part of a larger criminal organization. However, she did not discount the possibility that some of the victimizers may pretend to be part of organized crime groups to manipulate their victims.

Human trafficking cases have been particularly prevalent along the country’s northern border. Baja California recorded trafficking victims every year between 2017 and 2020, according to a diagnostic carried out by the National Human Rights Commission (Comisión Nacional de Derechos Humanos – CNDH) in collaboration with state and federal prosecutors specialized in human trafficking. The majority of those victims were young women and girls.

Both the CNDH report and other local analyses link trafficking dynamics in Tijuana and Baja California to its proximity to the US-Mexico border. The victims also share many characteristics. Whether they are migrants, transients, or members of marginalized communities, they are extremely vulnerable. This makes them increasingly susceptible to being targeted for sexual exploitation or forced labor.

For Navarro, a lack of awareness among the general public and government officials has contributed to the state’s ongoing struggle to combat human trafficking. Limited funding has also negatively impacted the efficacy of official investigations. She said more needs to be done to foster a culture of understanding in society to increase the level of awareness and empathy among investigators and prosecutors.

That said, such efforts often encounter deep-seated mistrust between the public and authorities due to one factor more than any other: impunity.

An Uphill Battle

There is little doubt that Adriana Lizárraga has the experience to lead the Specialized Investigation Unit to Combat Human Trafficking (Unidad de Investigación Especializada en Combate a la Trata de Personas) in Baja California.

She worked with victims of sex crimes in 2009, headed the state’s anti-trafficking unit two years later, and served as head of the Special Prosecutor’s Office for Gender-based Crimes Against Women (Fiscalía Especial para Delitos de Violencia Contra las Mujeres y Trata de Personas). She has conducted investigations into Mexican trafficking victims in New York and Florida, interviewed women from Venezuela and Colombia who were rescued from their exploiters in Mexico, and successfully lobbied for the inclusion of child pornography in trafficking laws.

However, the agency under her control has underperformed.

During the first quarter of 2022, Lizárraga’s unit opened investigations into only two cases of sexual exploitation and one case of child pornography. While proceedings were initiated in the first two cases, not a single conviction was secured. Lizárraga attributed the lack of results to a number of factors. She cited the shortcomings of her predecessor, who focused solely on team training without undertaking fieldwork or addressing complaints. The extreme dearth of data on human trafficking in previous years has also made her job more difficult.

Human Trafficking Victims Grow as Mexico Government Strategy Falters

But people have noticed the inaction. Dozens of relatives of missing people have protested in front of the prosecutor’s office on the Cuauhtémoc traffic circle. It may be in vain: Lizárraga says there is a specialized prosecutor’s office within the state that handles disappearances. What’s more, she said that trafficking is more closely linked to family-run operations than large, complex criminal structures.

“Most trafficking cases are categorized as organized crime due to the involvement of multiple individuals,” she explained. “However, in our context, it is more commonly driven by family networks. It is highly unlikely that large cartels … focus primarily on human trafficking. They may seek certain services, I won’t dismiss that possibility, but I don’t believe they are the main perpetrators behind it.”

Lizárraga highlighted one case she worked where an entire family engaged in the sexual exploitation of a young girl. To exert control, the victimizer’s mother-in-law cared for the victim’s daughter in Tlaxcala while the victim was being exploited thousands of kilometers away in Baja California. Lizárraga said this type of family network is common. When exploited women from the south of Mexico are separated from their children, this gives victimizers near complete control over them.

Despite her best efforts, she said, there have not been any criminal indictments or sentences related to these trafficking networks. Institutional shortcomings like being under-resourced and understaffed have overshadowed her good intentions, she added.