Over 60 Indigenous Miskito leaders and representatives are gathered in a Catholic church in the town of Mocorón, a village inhabited by approximately 500 Miskitos, located deep in the Moskitia, the great Honduran jungle in the department of Gracias a Dios, which borders Nicaragua.

The meeting is led by the priest Enrique Alargada, a small, slow-speaking Valencian Spaniard in his fifties, who has lived here for more than 20 years. The event has an anodyne name, one that would not arouse suspicions. It is the “Annual pastoral meeting for the environment.”

*This article is the third in a three-part investigation, “The Moskitia: The Honduran Jungle Drowning in Cocaine,” which analyzes how drug trafficking threatens one of the last jungle areas in Central America and the communities that live there. Download the or read the full investigation .

To attend the meeting, more than 50 representatives of different Miskito social groups traveled through the jungle for days. Among them are leaders of the town of Limitara, near the border with Nicaragua, and representatives from the Miskito women’s association, who traveled from Puerto Lempira, the capital of Gracias a Dios. There are also the women of the village of Mavita, where residents protect scarlet macaws from the poachers, driving them to extinction. They are joined by leaders from the territorial councils responsible for the defense of Miskito lands and at least two dozen other representatives of Miskito villages. In short, the Miskito people are well represented here, from the coastal and lagoon communities to the mountain villages.

Here, under the symbolic shelter of the church, these leaders discuss strategies to save their forest from the voracity of the “terceros” — the third parties — the name by which the Miskitos call the outsiders, the foreigners. The terceros they are referring to today have two particular characteristics. The first is that they are invading and destroying the Miskito jungle. The second is that they are linked to drug traffickers.

A Village Prepares to Fight

Alargada opens the meeting with a mass. He speaks perfect Miskito, but at the end of the homily he speaks in Spanish. He tells them that the Miskitos are like a biblical people; they have been promised a land by God and entrusted to take care of it.

“If we lose this land, if we allow them to take it away from us, in the future they will say, ‘What a foolish people the Miskito are. They let them take away the land and the riches that God gave them,’” he preaches.

One by one, men and women come forward to tell the others what is happening in their territories. Almost all of them speak of hundreds of hectares destroyed, of lands that have been illegally sold and invaded and through which they can no longer pass. Others tell how they were driven out of the same jungle where their grandparents and their grandparents’ grandparents had hunted and planted crops.

Then a young man asks to speak. He is large, with thick arms glistening with sweat. He wears the expression of a warrior on his face and walks towards the altar of the church as if doing a ring walk at a boxing match. He is not wearing the farmers’ work clothes that the others wear. Instead, he is dressed in a black shirt, tennis shoes, and jeans.

He is Miskito, but he is not a member of any of the organizations that are meeting today. He has been in the military, he says, and now he is here to organize the struggle against the terceros.

Almost everyone knows and respects him. His name has become well known throughout the jungle, among Miskitos and among the terceros, but in an effort not to be the one to put the target on his back, I will call him by another name, Miskut, like the mythological hero of the Miskitos. The man is a military-style strongman leader, a caudillo.

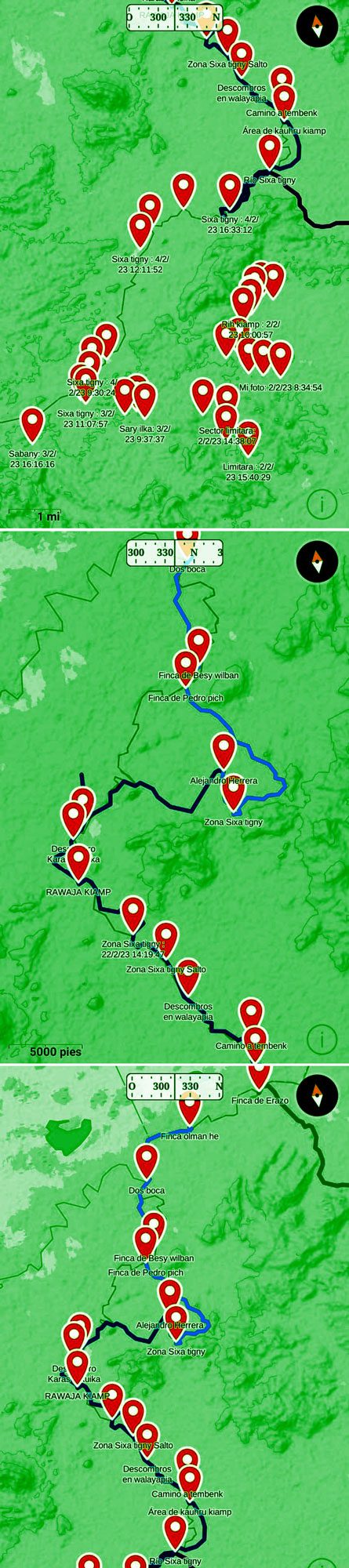

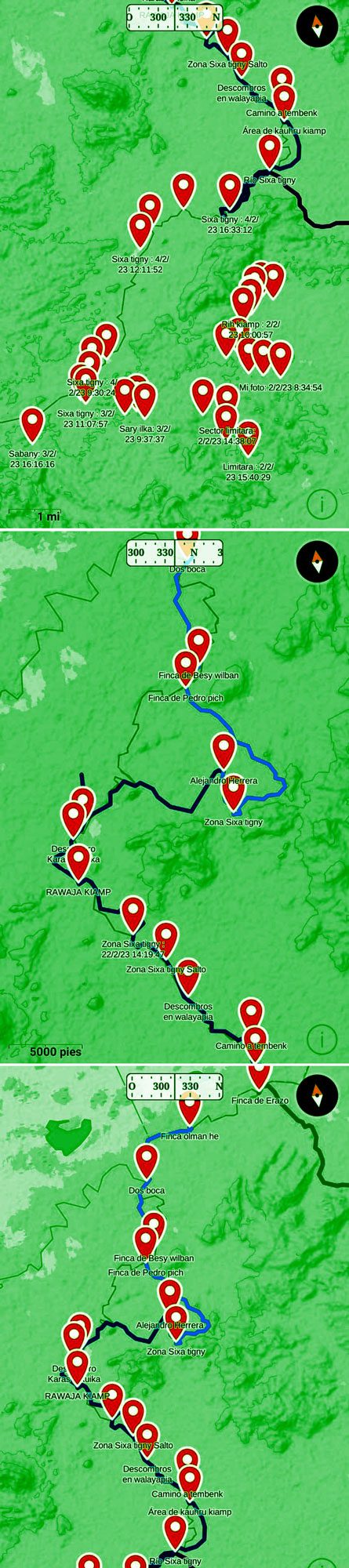

“I have come to show you, not to tell you,” he begins, as he presents a slide show. He tells them that together with the elders of the village of Mocorón, he has already made two forays deep into the jungle, “from Wisplini to Mavita,” he says, referring to a village more than 150 kilometers away from the meeting site.

“They don’t even take all the wood. They leave the mahogany to rot on the ground,” Miskut says. The murmur has become something difficult to decipher, a collective sound somewhere between lamentation and protest.

As Miskut speaks, a projector throws its bluish light on the wall of the church, where a crucified Jesus lies bleeding and motionless. It flashes apocalyptic videos and photos: hundreds of dead trees, endless charred plains where life once soared. A murmur of indignation runs through the church as he shows what was once a forest of mahogany, the sacred tree of the Miskito culture, from which they build their canoes and huts. The trees all lie dead on the ground. He says the terceros clearcut large tracts of land, driven by a desire to take over the Moskitia hectare by hectare.

“They don’t even take all the wood. They leave the mahogany to rot on the ground,” Miskut says. The murmur has become something difficult to decipher, a collective sound somewhere between lamentation and protest.

Miskut doesn’t seem to want to hold anything back. He points the finger at the representatives of the forestry institute, the only state entity represented at this meeting, and calls them useless. He accuses them of being accomplices of the apocalypse for not denouncing what is happening, for being lukewarm on the subject. He points to two women representatives of a group of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and says:

“The NGOs come to give us workshops, to tell us how to farm without damaging the forest and the ecosystem, to tell us to make home gardens to have food, and leave the mountain be. We already know how to do that, we have taken care of this jungle for more than 500 years! Why don’t they help us to stop the terceros, who destroy hundreds of hectares in one day?”

Miskut has a microphone, but he does not need it. The people he is referring to are in the front row, their faces lowered, and the reproachful looks of the Miskitos boring into their backs.

The images keep coming, one after another, dozens of videos showing desert where before there was life. Miskut continues to speak, the videos moving forward, the murmurs of the Miskito people already mingling with his words. An old woman cries out, as if in tears, and the officials and NGO representatives stare at the church’s exit, looking like they long to walk through it.

“There are also traitors among us,” he says, and points a resounding finger at Maximiliano, another name I will change for his own protection. Maxmiliano is a man in his 40s, sinewy, like most people around here. “He has been working for the terceros. He has been cutting down jungle on the side of Wisplini, and Mavita. I have the proof. He works for them.”

The crowd stirs and the first cries begin to sound out, it is already difficult to control them. Then Miskut says that everyone is at risk, that Maximiliano is some kind of spy, and that this puts the lives of everyone present in danger. To say this, in a place where leaders have received threats and been shot at by the terceros, undoubtedly puts the life of Maximiliano at risk.

Miskut drops the microphone and takes his strong body and his military stride outside. He passes by Maximiliano and looks him right in the face with the fury of a jaguar, then he leaves.

Maximiliano trembles, his nerves make him stutter. He takes the floor, grabs the microphone, and asks for forgiveness. He says that nobody is perfect, that if there is anyone here free of sin, let them cast the first stone. As he speaks, a communal booing drowns out his words. He pushes on, talking about everything he doesn’t have — money, food, work, and support. Then he talks of everything he does have — children and hunger.

But his excuses find little sympathy here. Those present are also hungry, and they have children. The church begins to empty, and outside, there is a commotion of screaming, angry Miskitos gathering around Miskut. From the look of things, it seems that Maximiliano will not come out of this well.

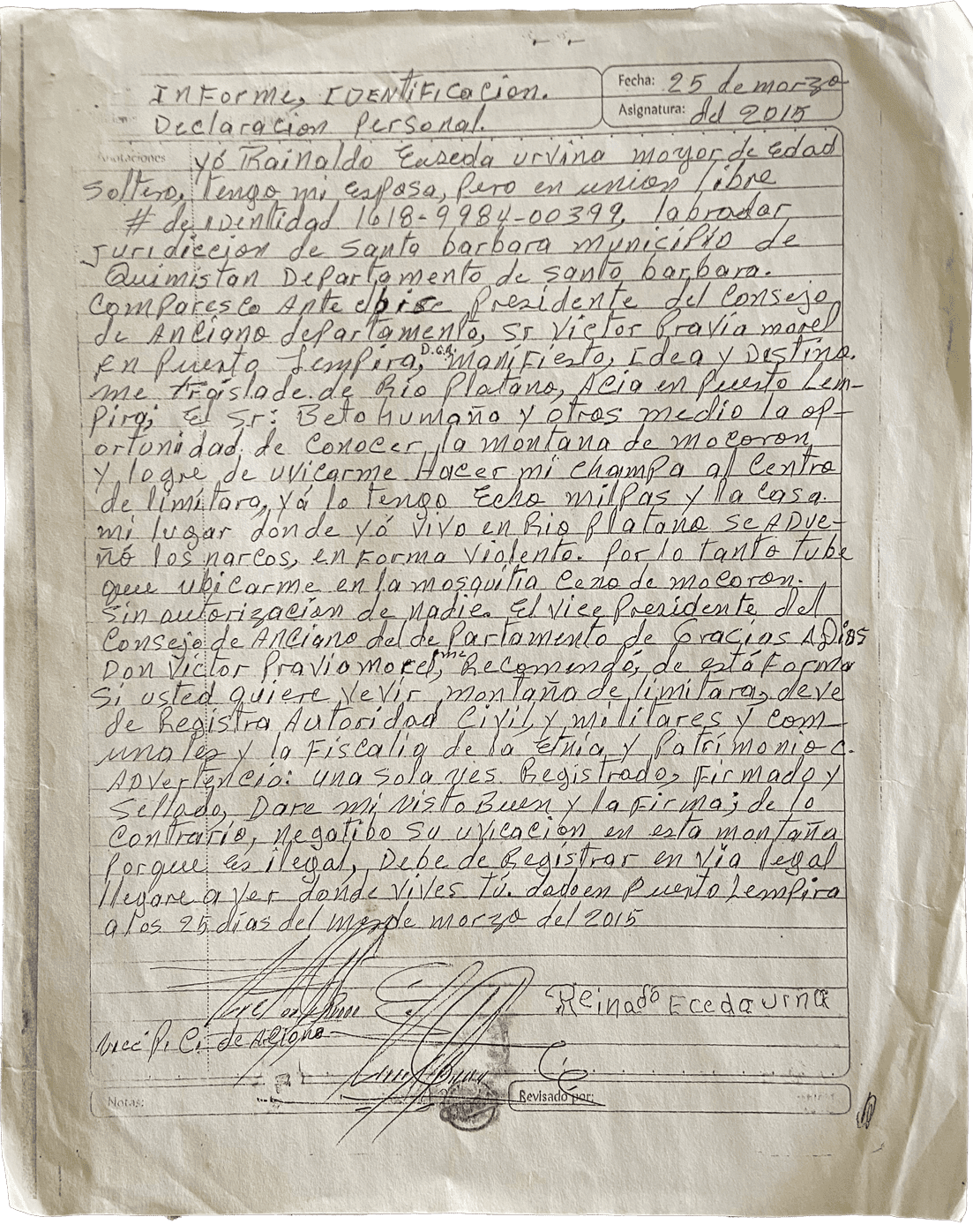

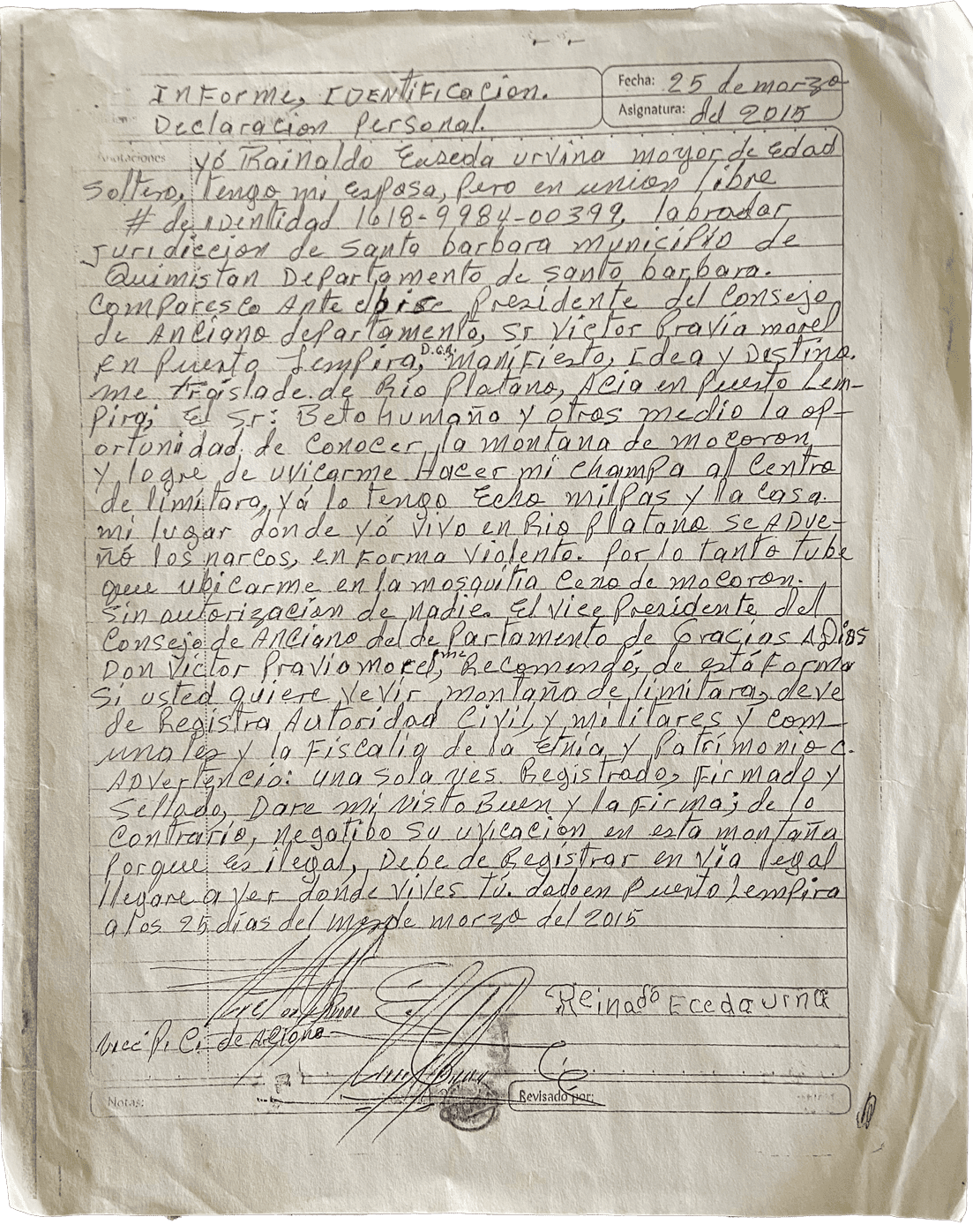

Photographs presented by Miskut at the meeting in Mocorón showing the remains of mahogany trees

Alargada takes the microphone and cools things down. The Miskitos, those who remain in the church, calm down. Then he blurts out a phrase, one of those that makes people cheer.

“We have to look at who we are really serving. If we want to place ourselves at the service of caring for our land, our children, and their future, we cannot also serve those who destroy it. If we want to serve our people and the people of the Moskitia … we cannot serve two masters.”

Outside, the commotion is loud. Maximiliano goes out another door and takes refuge in an evangelical church two blocks away, then he flees town.

In this story, Miskut and Maximiliano will meet again. But there are still three days to go before they do.

The Hunt

It is nine o’clock in the morning. A layer of dew fell at dawn, and the town of Mocorón has woken up to the smell of wet grass and wet earth. Two days have passed since the meeting in the church, and a group of Miskitos are preparing to go out into the jungle to hunt. This time, their prey will be people. They are going to hunt terceros.

Before leaving, the hunters eat plates of rice and boiled cassava that a group of women from the village have prepared for them.

It is a group of 16 people. Half of them are soldiers from the Honduran Army’s 5th Battalion. They are here because of an agreement between the Honduran military and the Indigenous communities of the Moskitia. It is one of the few expressions of support the Miskitos have received after sending so many letters and petitions. The government sends a squadron of soldiers to patrol the jungle from time to time, claiming that they are actively fighting deforestation and drug trafficking.

However, the government did not take into account that these soldiers are all Miskitos, and they believe, like everyone here, that if they do not stop the killing of the forest, their families and their children will face a very difficult future. That is why, today, they are rushing their rice and cassava so they can leave early and hunt in daylight.

It is Miskut who organizes everything. He has organized the civilian Miskitos, and he has persuaded the soldiers to accompany him, taking advantage of the agreement with the government. Miskitos in uniform and Miskitos out of uniform all follow the orders of the caudillo Miskut.

He rallies them loudly in Miskito, their native language, waving his hands and arms around as he tells these men how brave they are for what they are about to do. He tells them that the future of the Miskito people depends on the success of their mission.

Also traveling with the group is one of the council of elders of Mocorón village. His name is Abraham, he is 74 years old, and he walks through the jungle like rocks would walk if they could. He is tough, leathery, and compact. He walks without wheezing and hardly sweats. He energetically refuses when they offer him a hand to climb a hill or jump down a slope.

We set out on foot, in single file. It is almost ten o’clock when we cross the Mocorón River. Its waters are clear, and you can see a bed of leaves and branches at the bottom. Today, the waters are gentle because it is summer, the driest season of the year. This month, May, the first rains are expected to arrive to alleviate the thirst of the crops and the pastures and to swell the river, although every winter that happens less and less.

The Miskito soldiers cross in a canoe so as not to get their M16 rifles wet. I go with them while the others swim across. On their backs, each one carries about 40 kilograms of rice and cassava, and they take turns lugging a large aluminum cooking pot. They cross the river like it were nothing more than a puddle. This is the starting line. From here, far from their homes, the mission begins.

Abraham takes out a Bible and makes them form a circle. He reads, with some difficulty, Psalm 91 in Spanish: “My God, in whom I trust. For he will deliver you from the snare of the fowler and from the deadly pestilence. He will cover you with his feathers, and under his wings you will find refuge … A thousand may may fall at your side, ten thousand at your right hand, but it will not come near you.”

Then begins a hard trek through the virgin jungle that will last five days. The Miskitos, soldiers and civilians, push the pace. They want to arrive in the afternoon at the first point where they believe there are terceros clearing the jungle. They know this land; their fathers and grandfathers hunted here. But in those days, they were seeking less dangerous prey.

The group of Miskitos advances through the jungle quickly, it is almost impossible to keep up with them. The idea is to find the ruins of the jungle, to intimidate the terceros, and to take photo and video recordings, not only of the Martian landscape that remains after logging but also of the faces of the people who do it.

On the two previous occasions that they had gone out with the same mission, at the beginning of 2023, they surrounded several groups of invaders. One had taken over more than 600 hectares, an area the size of over 800 soccer fields. Another had taken over 500 hectares. But the videos show poor men, living in houses very similar to those of the Miskitos.

The Indigenous people elaborate theories about these newcomers. They associate them with traffickers because they have seen them working together, but they know nothing more. A high-ranking Honduran police commander who spoke to us on condition of anonymity said the strategy for invading the land is simple. They send groups of settlers to take over large tracts of land, give them the necessary tools to drive out the Indigenous people, and then, when they have occupied the land, they sell it to drug traffickers or to the frontmen the traffickers have on their payroll. The traffickers’ modus operandi is also described in official documents obtained by InSight Crime detailing two major anti-drug operations carried out in the Moskitia by the Technical Agency for Criminal Investigation (ATIC) and the Honduran Attorney General’s Office, Estegia I and Estegia II.

In the previous raid, in March 2023, Miskut and Abraham’s troop confronted a group of terceros, and were able to capture two of them. They took away their rifles and tied them up.

Witnesses who were there and were part of the troop told me that Abraham kicked the terceros and hit them with a stick while he made them point out on a map the places where the jungle had been destroyed. But the next day, after threatening them, they were released, leaving the Miskito people with two more enemies.

We keep moving forward. The jungle is good to those who know it and hostile to the outsider, to the tercero. We enter an area populated by evil bushes that stick whoever touches them with small thorns, which remain under the skin until the body finally rejects them and they work their way out on their own, causing much pain as they do. Contrary to popular imagination, the jungle does not offer accessible food sources. It is very rare to find fruit trees, and hunting an animal is a complex task that depends on being smarter and stronger than your prey. It is like a green desert. As we march, sudden gusts of wind stir the tops of the immense trees, where birds and monkeys watch us pass from their armchairs of branches.

It is mid-afternoon, the branches of the trees block the light, and the jungle becomes dark. We enter an area full of shifting mud, where the inexperienced foot sinks slowly as the mud drowns you and you are lost forever in the bowels of the jungle. More than once, Miskut’s hand lifts me up like a child from the clutches of the mud. My presence only delays the troop. Every mistake of mine means valuable minutes lost. The sound of my boots on the rocks and the clink of my pack will eventually give away our position, if it hasn’t already. I believe, moreover, that they do not want to hunt in front of the eyes of a stranger, in front of the eyes of a tercero. Miskut tells me that he and I will return to Mocorón. I obey him without complaint. Old Abraham will lead the troop in their search for enemies.

In Search of Allies

Miskut has an important mission. But it is a risky and secret mission. He must talk to the elders of Mavita, another distant village whose leader, after resisting the illegal logging of pine trees, was ambushed by a group of hired killers. He survived, but afterward he decided with the village elders and young leaders that they would barricade themselves in their village. There is no phone signal, and the only way to find them and enlist them in the war for the jungle is to go there and convince them in person.

Miskut will let me accompany him in exchange for buying something that, at this point in the jungle, has become almost a treasure: gasoline. The only way to get there is on his motorcycle. It is a road formed by the feet of the Miskitos who have traveled it for decades, perhaps hundreds of years.

Miskut asks me not to tell anyone we are going because we must avoid an ambush. But no one buys gasoline to stay in the village. “These people have ears everywhere,” one of the elders had already warned us, referring to the traffickers’ local informants. And it’s true, they do. The next day, we would find out.

Our presence here has not gone unnoticed. Four days ago, while talking at night with a group of elders from Limitara who had come for the meeting, we discovered that we were being spied on by a boy. No one there knew him, and when we asked him who he was and why he was eavesdropping on us, he ran. We followed him, but he dissolved into the jungle like a ghost.

Miskut and I leave through the back of the village as stealthily as possible, taking a disused road that is longer, but safer.

The bike is large, with special dirt tires. Miskut drives it like an extension of his body and reaches speeds of 80 kilometers per hour. He carries a .38 caliber revolver, but it is no guarantee of our safety. Although it is a large caliber, it only holds six shots, and he must use both hands to drive.

Along the drive, the landscape changes from rainforest to coniferous forest, with towering pines and grasslands climbing to the top of the mountains and hills. The pines stretch as far as the eye can see. If it weren’t for the thin path we are moving along, it would seem as if no one had ever been here. Everything is in a state of natural disorder. It is like walking through a brand-new world.

Two hours into the trip, the narrow trail intersects a larger one. Miskut stops the bike in front of a rough cement cross.

“This is the place where Osvaldo Jacobo was killed,” he says, staring at the cross. Osvaldo was one of the Moskitia’s first environmental defenders. He was a biologist, and when confronted with the imminent destruction of the forest in the late 1990s, he created the first Miskito organization to defend the Moskitia and all it contains, Miskitos included.

“Osvaldo had to be taken out of there with a shovel,” his sister told me a few days ago. According to his family and neighbors, on December 27, 2000, Osvaldo stopped his motorcycle because a tire blew out. While he was trying to fix it, a pickup truck ran over him several times, leaving only an indistinguishable mass that the vultures ate for days, a mass that his relatives had to shovel into plastic bags so they could bury him in the town of Mocorón.

Osvaldo had previously received threats for obstructing logging and standing in the way of the power of drug traffickers. He began to organize the Miskitos and sought a series of alliances with organizations in Honduras’ capital, Tegucigalpa. That day he was on his way to Mavita, the same village we are heading to now, to do something very similar to what we are planning: talk to the most respected and feared Miskitos in the jungle, the Lakut.

Miskut made this cement cross with his own hands as a tribute to Osvaldo. He believes he will end up the same way. Fate will decide if someone also makes a cement cross in his honor when he dies. We return to the motorcycle, still several hours away from our destination.

It is late afternoon when we cross the small river that separates the village of Mavita from the rest of the Moskitia. The forest ends, and a gigantic garden begins. We are entering Lakut territory.

The noise of our motorcycle breaks the peace of the village and causes a whirlwind of colorful wings to rise up. It is as if a rainbow had been shooed away. Dozens of scarlet macaws live here, protected by the Lakut family, the founders and guardians of this piece of paradise.

It is not a large village. The locals say that grandfather Lakut arrived to this land, then sparsely populated by pines and macaws, at the end of the 1950s. He had been here while he was a soldier, fighting in the ephemeral and malnourished war between Honduras and Nicaragua for the control of the Moskitia. After the war, he returned, built a house, and had children. His sons found wives, and his daughters got husbands, and today the village has more than 200 inhabitants. They live much as the humans of this region did three thousand years ago. They grow cassava, corn and beans and supplement their diet with fish and wild game.

But what makes this village unique in the whole of the Moskitia is that living alongside the Lakut are the scarlet macaws. The idea of saving this species was born in Rus Rus, a neighboring village. There, a man called Tomás Manzanares started to breed macaws and take care of their nests. But to take care of the nests, it is necessary to take care of the trees that house them, and, it turned out, those trees were worth money. Unlike in other parts of the jungle, in this area the traffickers have a system in place to cut down the pines and sell them in the department of Olancho or across the border in Nicaragua. As a side business, the loggers also sell the macaws and their chicks to other traffickers, who then take them to Colombia and Jamaica.

The macaws and the pine trees where they make their nests are still worth gold, and in this jungle, in a rare formula of alchemy, gold attracts lead.

The rule seems to be that if something is worth money in the Moskitia, then sooner or later the terceros will arrive. For Manzanares, defending the macaws cost him dearly. In 2011, a tercero shot him four times and left him bedridden for four months.

With Manzanares out of the way, the macaws were captured and sold, and the trees where they make their nests were cut down and sold. The die seemed to be cast for those animals. So Manzanares decided to do the same thing that Miskut is doing now: seek the support of the Lakut. He spoke in 2011 with the Lakut family’s council of elders and asked for shelter for the few specimens that survived the slaughter and sale.

The Lakut elders decided to give shelter to the macaws, and since that day, they have lived among them. They eat the same beans, rice, and cassava as the Lakut, and have their nests in the trees protected by the family. This is how the grandmothers and mothers of the macaws that flutter around us today first arrived here. But the macaws and the pine trees where they make their nests are still worth gold, and in this jungle, in a rare formula of alchemy, gold attracts lead.

Lakut Warriors

Santiago Lakut is head of the council of elders of the Mavita village. He is a strong man, well into his fifties, with skin as dark as an ebony tree. Santiago, like his grandfather, the founder of the village of Mavita, knows about wars. He fought in the 1980s in Nicaragua on the side of the Contras, a guerrilla group financed by the US government that sought to overthrow the socialist Sandinista regime. This knowledge of warfare and the weapons at his family’s disposal is what makes him so indispensable in the fight against the terceros.

He shows off a bullet pulled from the underside of the windshield of his truck.

“I was driving with my son when suddenly we started hearing gunshots. There were two of them. My son said to me, ‘Dad, what is that?’ ‘They’re bullets. Get down,’ I told him, and I came here without stopping,” said Santiago.

At night, the Lakut have given us the same dinner as their macaws: rice and beans. Santiago and the other elders receive Miskut in a remote part of the village. We sit on some pine planks while Jurassic-sized mosquitoes drain our blood, and they ask Miskut to let it all out, to tell them what brought him here.

Miskut respectfully greets the three elders, and before speaking, he alludes to the fact that although it is a remote connection, he also carries the surname Lakut in his name. He then apologizes to me, he will speak in Miskito to the elders. Whatever he is going to tell them needs privacy. They talk for more than an hour, sometimes in the soft, harmonious tone of their language, sometimes with expressions and expletives borrowed from Spanish or English. Santiago and the elders refuse whatever Miskut asks of them. Miskut insists. They shake their heads and frown, look at each other, clearly worried. They say no.

After a while, the discussion seems to have reached an impasse. Miskut, skilled in persuasion, takes out a powerful weapon: his phone. And one by one, he shows them the photos he took during the two previous raids. Hundreds of felled mahogany trees rotting on the ground, charred animals, victims of the fires set by the terceros, videos where workers captured by Miskut’s troop of Miskitos admit that over the last few weeks they have cut down between 400 and 600 hectares of forest to bring in cattle. There is sadness in the eyes of the Lakut.

He shows them the low flow of the Mocorón River and talks about how, where before they had to struggle to avoid being capsized in their canoes, now they have to try not to run aground. He reminds them that if the forest dies, the rivers will dry up, and if this happens, each village will be cut off since they will no longer be reachable by canoes. Then, yes, each village in its solitude, will have to come to terms with the terceros. Even the brave Lakut will be defeated at some point.

Lakut community leaders look at photographs of land invasions and the destruction of the forest in the Moskitia.

The Lakut look on in silence, dumbfounded. They approach Miskut’s phone like they are gathering around a bonfire and point their fingers. They ask to see the map that Miskut has made with georeferenced locations of the places where the terceros are concentrated. They are no longer learning, now they are planning. The sadness has become something else.

It is late at night, and they finally return to Spanish. They tell me they are willing to exhaust all peaceful means to expel the terceros from the jungle. They are going to pressure the government to fulfill its longstanding promises to “clean up” their lands, which basically consists of sending the military to expel the terceros. But if this fails, there will be no other way out but to fight.

An Ambush in the Jungle

The next morning, the village wakes up to the cries of the macaws. One peeks over the railing of my window and squawks at me, as if asking me for something. Outside, a woman from the Lakut family trudges along carrying a huge pot full of food. The macaws hover over her, shrieking thunderously. From a distance, she looks like some kind of goddess of color and flying animals. With a ladle, she serves them rice and beans on a table, the same thing she will eat for breakfast, and the animals make a swirl of feathers over the food. They sound like they are laughing.

In the afternoon, the Lakut will serve them another pot of the same menu, thus ensuring that the macaws stay close to them, under their protection, and that they do not have to risk foraging for food where the poachers can catch them. If any tercero ventured to hunt macaws or log pine in the vicinity of Mavita, they would have to engage in a shooting match with the Lakut, and this is something the traffickers do not want, at least not right now.

The Lakut family receives some support from international animal conservation organizations that help them with money to keep the birds, but it is not enough. And, above all, they do not provide any help in protecting them from poaching and deforestation. If it were not for this family, and before that, for the brave Manzanares, there would be no more scarlet macaws in this forest.

We get on the motorcycle again. A journey of several hours through the jungle awaits us. The elders point us to a forgotten road, they think we will be safer there. They entrust one of the teenagers of the family as our guide and give him a shotgun and a motorcycle. The boy takes us on the old road, made by his grandparents, walking so much in the same place. Reaching the limit of Mavita’s territory, he tells Miskut where to go. In the distance, we can still hear the laughter of the macaws.

The road is difficult, we have to get off every so often to adjust the chain of the bike, which slips off with every stumble or rock. The jungle is quiet; just a trembling wind moving some leaves and the song of a bird that can be heard in the distance. We stop at Casa Sola, a small hamlet of three houses where a tercero family with whom the Miskitos have a good relationship lives. Miskut gets off and says hello, he wants to show me something.

“We have no problem with them coming to live here. There is land here. As long as they live like us, that they take one or two hectares and grow crops for a living, we welcome them. But if they want to come and cut down 500 hectares for one man and then sell it and expel the Miskitos, then they are not welcome,” he tells me.

We drink the water offered by a silent woman and return to the bike.

Less than an hour after leaving Casa Sola, suddenly, in the middle of a wide road, there is Maximiliano, the man Miskut accused in public of being a traitor. There are five other men with him, and they all carry machetes.

Fear is a powerful thing, it plays strange games in the head. In mine, it stops time, dilates my pupils, making me see everything much brighter and much slower. It dries my mouth and paralyzes my hands. Miskut tenses, I feel it in his shoulders, and he accelerates the bike. He emits a kind of faint, animal-like growl and says, more to the air than to me, “He doesn’t have the balls. He doesn’t have the balls.”

Environmental Crime News

He doesn’t. They are left standing when Miskut shoots past like a bullet. Maybe they were expecting one rider and not two. Maybe the message from the famous “eyes and ears” wasn’t accurate. But whatever stopped them from attacking was short-lived. Two of them get on a motorcycle and start it up behind us. I think about how if the chain slips, as it has been doing the whole trip, they will catch up with us. I think about the six bullets in Miskut’s revolver.

“No. He doesn’t have the balls. No,” Miskut repeats like a mantra as he speeds his motorcycle over gullies and streams.

The motorcycle of the two men is smaller, we lose it every so often, but in the curves or coves, where we must go slower, we see them appear about 60 meters behind us. Suddenly, among the trees, we can see the smoke rising from the wood stoves of Mocorón. The men give up. Mocorón is resistance territory.

The Uncertain Fate of the Miskito Nation

Violence is rarely a migratory bird passing through. It nests in places and in people’s hearts for a long time. It has been in the Moskitia for almost 30 years, and everything indicates that it will not be gone for a long time. But violence needs to stop being an idea and become a reality. It needs tools, and it is not a one player game. It also needs organization and resources. The Miskitos have accepted the invitation to violence, but they do not yet have all of the above to carry it out efficiently.

What would a war against the terceros look like? I asked Eusebio, a member of the Mocorón council of elders, a week before the trip to Mavita.

Don Eusebio answered very convincingly. They have bows, arrows, and spears, he said. He believes that just as an arrowhead enters the flesh of a deer, it will also enter the flesh of a man.

In the village of Mavita, near the end of our conversation, which was long, as Miskito conversations usually are, I asked the same question to the Lakut elders. They do have firearms, but they are few in number and mostly 12-gauge shotguns — a powerful weapon for hunting or self-defense, but not very efficient for a confrontation against AR-15s, AK-47s and the M67 grenades of terceros and cocaine traffickers.

“They have weapons, it’s true, because they have more money from drug trafficking. But we have strengths too. There are many of us and we are organized, we know the jungle. Besides, we have silent weapons, we have slingshots and arrows. I’ll kill you without noise!” says Hector, one of the three Lakut elders.

Then another, driven by euphoria, says, “We have sica.” The others turn to look at him, as if reproaching him for revealing their secrets. But after a while, they agree to tell me about their secret weapon, with which they plan to confront the teceros.

“Sica is a prayer. I do sica on you, I put you to sleep. Or I make myself invisible and kill you with a dagger, easy,” says Santiago, the chief of the Lakut elders.

They tell me sica is a kind of spell that is expressed in various forms. One must say the right words in the right order and mark a cross in a certain place. The enemy who passes by that place will be filled with hatred, and he will carry that hatred to his house, thus sowing discord among his own, and they will end up killing each other. According to the Miskitos, it also serves to make the enemy miss with their shots and jams their weapons.

The bow and arrow, concludes Dr. Antonio Rodríguez Hidalgo, an authority on the recent past of the human species, began to be used in the Mesolithic era, after the last ice age, in almost all the world except Australia. Its use became popular among hunter-gatherer societies about 12,000 years ago. So, if we get strict in terms of warfare technology, the terceros have a 12,000-year head start on the Miskitos. It is as if a Paleolithic people were facing a modern army.

The shots are already ringing out here. They are lodged in Santiago Lakut’s car, in the bodies of the biologist Manzanares and a handful of Miskito leaders. They fall from the sky from the helicopters of the Honduran army and hit children and adults without distinction. They sleep, waiting in the shotguns of the Miskitos and the AR-15s of the traffickers. The first dead have already been buried, for the moment, on one side only, the Miskito side.

The troop that went out to patrol the jungle commanded by the elder Abraham returned with devastating information. More destruction, more fires, more terceros. Hundreds of hectares that a few days ago were a jungle teeming with life are now barren fields where cattle roam and cocaine planes land. What they found on their expedition further fuels the Miskito people’s conviction to fight.

While the future is uncertain, that of the Miskitos is predictable. They face forces they themselves do not understand, powerful men with an immeasurable capacity for violence and with resources to spare to finance it. Darkness is coming. Time will tell what the fate of the Miskito nation will be. For the moment, all we can say is that a handful of Indigenous peoples are preparing for war on the banks of the Mocorón River.

Continue reading this three-part investigation:

Investigation credits:

Written by: Juan José Martínez d’Aubuisson, Bryan Avelar

Edited by: Steven Dudley, James Bargent, María Fernanda Ramírez, Peter Appleby

Fact-checking: James Bargent, María Fernanda Ramírez, Chongyang Zhang

Creative direction: Elisa Roldán Restrepo

Chapters layout and video editing: María Isabel Gaviria

PDF layout: Ana Isabel Rico

Graphics: Juan José Restrepo, María Isabel Gaviria, Ana Isabel Rico

Photos and videos: Bryan Avelar, Juan José Martínez d’Aubuisson