It was mid-October 2022 when Felipe,* a heavily-tattooed former member of El Salvador’s largest street gang finally escaped the government’s clutches.

Like scores of gang members and affiliates, Felipe, 49, had gone underground in the midst of a Draconian security crackdown launched by the administration of President Nayib Bukele six months earlier.

*This article is part of a six-part investigation, “El Salvador’s (Perpetual) State of Emergency: How Bukele’s Government Overpowered Gangs.” InSight Crime spent nine months analyzing how a ruthless state crackdown has debilitated the country’s notorious street gangs, the MS13 and two factions of Barrio 18. Download the or read the other chapters in the investigation

Coined the régimen de excepción, it was the government’s latest attempt to confront the country’s main gangs — the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and two factions of Barrio 18 — with force. It was familiar territory for the gangs, who during security campaigns dating back to the 2000s had traded bullets with security forces or targeted individual police officers or soldiers.

But things were different this time. Since the crackdown began, the gangs had shown minimal signs of armed retaliation. Rather, in a matter of months, Bukele’s crackdown had swept up tens of thousands of suspected gang members and affiliates.

With gang structures crumbling fast, Felipe and others not caught in the arrests were left with little choice but to run or to hide.

Felipe, a retired member of the MS13, did both. He first found a hideout. Then, when the speed of government arrests failed to subside, he made plans to flee the country. Strapped for cash, Felipe looked to church groups that had previously helped him distance himself from the gangs.

They bought him a bus ticket, and, on October 15, he embarked on a three-day road trip to southern Mexico, where he and other gang retirees rented a house nestled in the mountains of Chiapas state.

In fleeing El Salvador, Felipe joined a long list of current and former gang members seeking refuge abroad, mainly in Mexico, Central America, and the United States. Others, lacking travel funds or a means of safe passage, remain in hiding in El Salvador.

InSight Crime spoke to a number of current and former gang members with similar stories. All shared the immediate concern of avoiding arrest or deportation.

“The important thing is they don’t send me back to Central America,” said Felipe, who was detained when he later attempted to cross from Mexico into the United States. He now faces possible deportation.

Neither Felipe nor any of his counterparts had ambitions to counter the Bukele government. Instead, perhaps for the first time, they were humbled and scrambling.

Vanishing Act

The gangs’ primary reaction to Bukele’s crackdown appears to have been to go into hiding.

An internal intelligence report compiled by the Salvadoran anti-gang police unit at the state of emergency’s onset concluded that the MS13’s top leadership ring in El Salvador, known as the ranfla, had ordered gang bosses and fully-fledged gang members (homeboys) to either seek refuge in safe houses, mountainous areas, and private residences, or attempt to flee to neighboring countries and wait for the crackdown to subside.

But during nine months of research, InSight Crime found no signs of a coordinated, violent response, a stark contrast to the bloody clashes between gangs and security forces during previous state crackdowns.

Instead, gang members have scattered. Some street-level members and gang collaborators have seemingly remained in El Salvador, lying low with relatives or seeking refuge in areas outside of major urban hubs with associates or allies.

The gangs’ sudden disappearance was corroborated by dozens of residents in former gang strongholds in San Salvador, Apopa, Soyapango, Illopango, Mejicanos, Ciudad Delgado, San Julián, Tonacatepeque, and San Miguel. None of the residents said they had witnessed any kind of response from gang members, armed or otherwise, aimed at protecting territories or securing their criminal economies.

One community worker in Apopa said some gang lookouts, once a ubiquitous presence in the area, were now monitoring the territory from their residences to avoid arrest.

Residents in Mejicanos told InSight Crime that children and adolescents who once collaborated with the gangs still roam the streets. But they are no longer feared by locals, and it is unclear whether they are still patrolling on behalf of the gangs.

Bus company directors and drivers in the San Salvador metropolitan area, among the most common victims of gang extortion and murders prior to the state of emergency, also told InSight Crime the gangs no longer interfered in their day-to-day operations. A trio of bus drivers interviewed by InSight Crime at one bus depot agreed the gangs had, for the time being, “disappeared.”

The Gangs Migrate

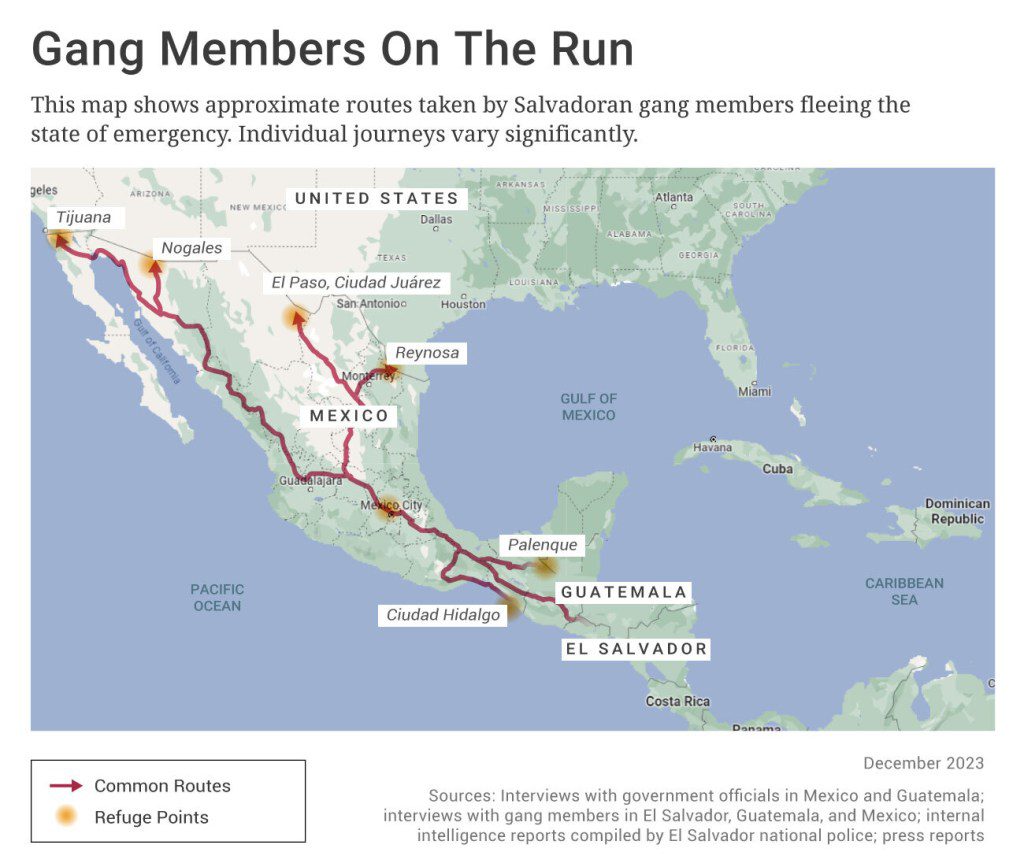

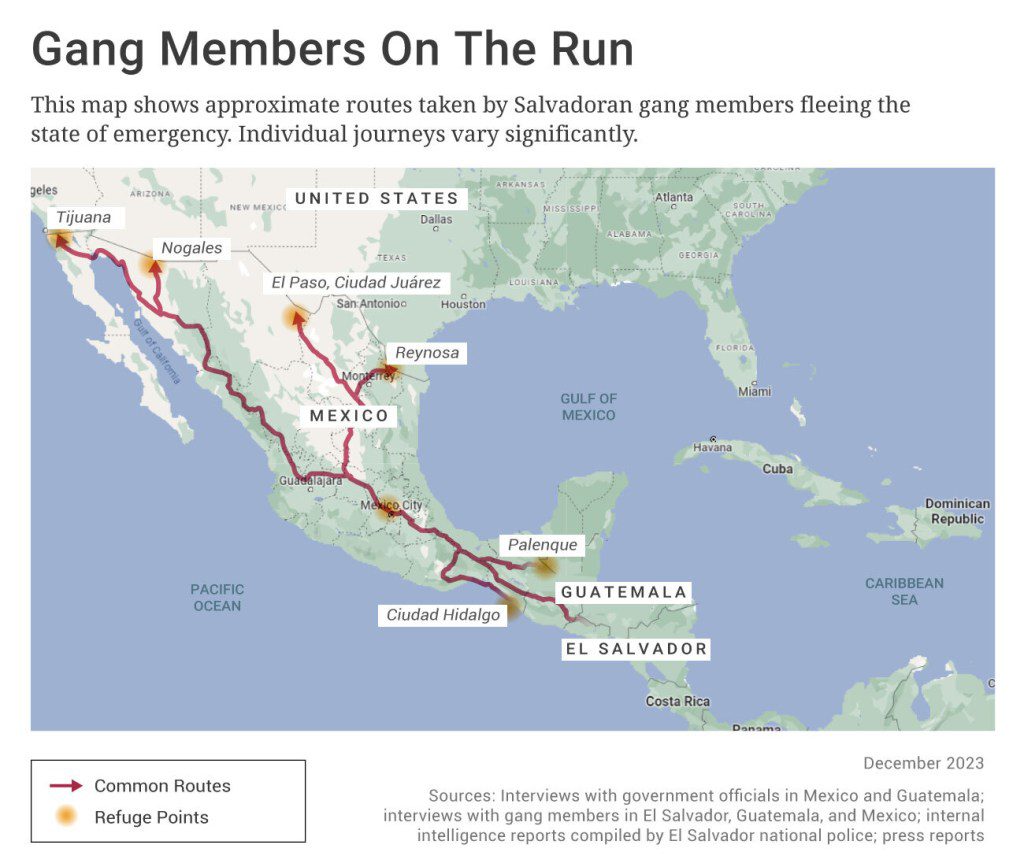

The threat of detention has also led many active and semi-retired (often termed, calmado) gang members to flee to nearby countries along well-established migrant routes passing through Central America and Mexico toward the United States. These routes have long provided a means of escape for gang members in El Salvador facing aggressive security campaigns or possible arrest. But anti-gang police in neighboring countries such as Guatemala have strengthened their border surveillance following Bukele’s anti-gang crackdown, making passage more difficult.

In addition, embattled gang structures in El Salvador appear unable to provide meaningful support to street-level members fleeing the country. Rather, gang members appear to be relying on their savings or family funds to finance their escape or to provide temporary respite.

One calmado now in Mexico told InSight Crime he arrived in the country after purchasing his own bus tickets to travel through Guatemala. Others, hoping to reach the United States from Mexico, were saving money to hire a human smuggler at a cost of around $5,000.

For some, like Felipe, fleeing El Salvador came after several months of hiding. Gang members in Mexico said many of their colleagues are still in El Salvador, unable to muster the funds to head north following disruptions to key gang economies like extortion.

This does not mean that gang members do not rely on one another for support. Some MS13 and Barrio 18 members fleeing El Salvador have been housed by other gang members or their extended networks in Guatemala and Mexico.

One calmado on the run told InSight Crime he had sought help from a contact to cross the Suchiate river, which divides Guatemala and Mexico and appears to be a common route for Salvadoran gang members seeking to enter the state of Chiapas in southern Mexico. Police in Chiapas told InSight Crime they had noticed an uptick in gang member arrests since the start of the state of emergency but did not offer data to support this assertion.

Salvadoran gang members living in Mexico have also provided refuge for active and semi-retired gang members. A jailed member of the MS13’s main umbrella group in Mexico, known as the “Mexico Program,” told InSight Crime the group had received various colleagues fleeing El Salvador, but these members were only those who had been granted authorization to seek refuge in Mexico by members of the Mexico Program and their trusted gang contacts in El Salvador.

Meanwhile, in Central America, members of the MS13’s ranfla have reportedly asked gang bosses in Guatemala and Honduras to provide refuge for those fleeing El Salvador, according to an internal report compiled by Salvadoran anti-gang police shortly after the state of emergency began. The same report claimed MS13 members were already seeking refuge in Guatemala City and the surrounding urban area, including in existing gang hubs like the Mixco and Villa Nueva municipalities.

It is hard to gauge the extent to which these orders were implemented. But an MS13 member based in Mexico told InSight Crime that one of the gang leaders mentioned in the official report had contacted him from Guatemala about helping gang members reach Mexico, which has become an attractive destination for gang members on the run.

Four semi-retired Salvadoran gang members told InSight Crime they were able to acquire a humanitarian visa in Mexico by claiming to be victims of gang violence and covering their tattoos. This suggests a degree of leniency from officials not common in Central America, where authorities are more familiar with the gangs and make arrests based on appearance or loose gang affiliation.

One active MS13 member based in Tijuana said gang members attempting to reach Mexico were struggling to cross Guatemala in the face of indiscriminate arrests. “If the [police] see your tattoos, they’ll send you back to El Salvador,” he said.

The head of Guatemala’s anti-gang police, Ángel Cambara, told InSight Crime that “any arrested gang member from El Salvador is immediately sent back.”

Criteria for identifying potential gang members includes checking suspects for tattoos and contacting Salvadoran authorities to verify gang status, Cambara said. He added: “The majority have a criminal record or a pending arrest warrant.”

Though gang members appear to be moving to and through Mexico in large numbers, Mexican authorities only reported 36 deportations of suspected Salvadoran members of the MS13 and Barrio 18 between April 2022 and May 2023.

Meanwhile, Guatemalan police had reportedly expelled 70 suspected gang members from El Salvador fleeing the state of emergency as of mid-December 2022. A further 64 were deported in the first nine months of 2023, according to police data reported by Prensa Libre. Official Guatemalan reports largely coincide with these numbers. Guatemalan police also arrested a total of 73 suspected Salvadoran gang members between January and September 8, 2023, according to the Prensa Libre report.

In at least three cases, Mexican authorities have delivered Salvadoran MS13 and Barrio 18 members, detained in Mexico, to Guatemalan officials manning customs checkpoints on the shared border; Guatemalan officials then transported the detainees overland to the country’s border with El Salvador and into the hands of Salvadoran authorities.

Some semi-retired gang members who made it to Mexico told InSight Crime they planned to continue traveling to reach family in the United States. Family reunification is a common driver of migration from Central America to the United States. This is no different for gang members who have possible ties through family and their gang; the MS13 and Barrio 18 both began in California, and millions of Salvadorans reside in the US. But attempting to enter the United States also carries the risk of deportation, in addition to expensive smuggling fees associated with crossing the US-Mexico border, deterring some from venturing beyond Mexico.

InSight Crime sent an information request for figures on deported Salvadorans with gang connections to United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) but had not received a response by the time of publication.

Gangs Abroad: Lying Low

While many gang members have fled El Salvador, most do not appear to be taking up their criminal activities abroad.

Press reports from 2023 pointed to a possible increase in extortion perpetrated by Central American gangs, including the MS13 and Barrio 18, in towns on Mexico’s southern border. However, when InSight Crime investigators in Tapachula, Chiapas, asked residents about the reports of gang extortion, most said the extortionists were Guatemalans, not Salvadorans fleeing the state of emergency. And despite reports of extortion, the Chiapas Attorney General’s Office did not prosecute any MS13 or Barrio 18 members between October 2022 and February 2023.

In fact, active MS13 members based in Mexico told InSight Crime their Salvadoran counterparts are lying low and opting out of criminal activity to avoid drawing unwanted attention to themselves. Likewise, semi-retired gang members hiding in Mexico or hoping to reach the United States told InSight Crime they had little intention of re-entering gang life.

The gangs that are already established in those areas also appear to be keeping their distance from Salvadoran gang members. The MS13’s Mexico Program, for example, has so far been reluctant to recruit gang members fleeing El Salvador for criminal activity given their heightened exposure to arrest. And an MS13 member from Mexico, based in Tijuana, told InSight Crime that few Salvadoran members were reporting their arrival to the gang.

Although authorities in Chiapas, Mexico, which borders Guatemala, arrested 50 Salvadorans suspected of being members of the MS13 and Barrio 18 between January and September 2022, data provided by Chiapas authorities shows there has been no significant increase in MS13 members jailed in the state’s prisons since the start of the state of emergency. As of June 22, only 11 of the 90 MS13 members housed in Chiapas prisons were Salvadoran nationals.

The situation is similar in Guatemala. The head of Guatemala’s gang police told InSight Crime there has been no spike in gang-related crime as a result of the state of emergency. There are also few signs that fleeing Salvadoran gang members are attempting to re-engage in criminal activity by joining gang cells in Guatemala.

One Guatemalan MS13 member housed in the Pavoncito detention center, a notorious prison just south of Guatemala City with a significant gang presence, said the gang’s Salvadoran diaspora has not altered the group’s structure on the streets or behind bars. This was echoed by the head of Guatemala’s anti-gang police. The MS13 source added that the presence of Salvadoran gang members in Pavoncito is practically irrelevant. The source estimated that around ten Salvadoran gang members had passed through the jail before being deported back to El Salvador following the onset of the state of emergency.

The arrival of Salvadoran gang members to the United States does not appear to have altered gang dynamics in that country either. There has been no notable increase of Salvadoran MS13 or Barrio 18 members in states or prisons where the gangs have a presence, a source from the US Federal Bureau of Prisons told InSight Crime. Alex Sánchez, head of Homies Unidos, a California-based NGO that works to reduce violence in communities impacted by gangs, said Salvadoran gang members arriving in the United States are lying low rather than engaging in criminal activity.

Honduras, despite bordering El Salvador and having a strong presence of the MS13 and Barrio 18, does not appear to be a major refuge for gang members fleeing El Salvador. Honduran authorities told InSight Crime that they arrested just six Salvadorans with suspected gang ties between January and September 26, 2023, compared to 23 the previous year.

The situation may be different for top gang leaders. Internal intelligence reports compiled by El Salvador police in April 2022 claimed MS13 leaders were traveling to Mexico to plan a response to Bukele’s policies. InSight Crime could not corroborate this, but multiple reports point to the presence of gang leaders in Mexico.

Prior to Bukele’s crackdown, for instance, the United States government had accused MS13 leaders of moving to Mexico to expand operations. And, in November 2023, a veteran gang member considered by many as the MS13’s second-in-command was arrested in Mexico and extradited to the United States.

Back in El Salvador, top MS13 and Barrio 18 leaders have been conspicuously absent from government social media accounts, which have been actively publishing photos, videos, and reports of mass detentions during the crackdown. Just months before the state of emergency began, the veteran MS13 leader now facing justice in the US reportedly leveraged his political connections to escape prison in El Salvador and flee the country. The MS13 leader was one of four released from jail between July 2021 and February 2022, despite facing extradition to the United States.

In addition, arrests of gang leaders accounted for just 1,232 of more than 77,000 reported arrests (around 1.5%) made during the state of emergency as of September 30 2023, according to an El Salvador police intelligence report obtained by InSight Crime and arrest figures announced by Salvadoran officials. Authorities reported the arrests of 945 MS13 cabecillas during that time-frame, compared to 287 for the two factions of Barrio 18 and other gangs, according to the same intelligence report.

The El Salvador government has yet to extradite any MS13 leaders, despite many being wanted by US authorities. The whereabouts of many gang leaders remain unknown, but so far InSight Crime has not found evidence to suggest this is linked to any dialogue, pacts, or truces with the Salvadoran government.

*Felipe’s name has been altered on request to preserve his anonymity.

*With additional reporting by Steven Dudley, Carlos Garcia, César Fagoaga, Bryan Avelar, Roberto Valencia, and Juan José Martínez d’Aubuisson