The road to El Salvador’s state of emergency has been long and bloody.

The small Central American nation spent decades engulfed in some of the most intense spates of violence in the Western Hemisphere, as the country’s three main gangs — the Mara Salvatrucha (MS13) and the two factions of the 18th Street, or Barrio 18 — waged bitter wars amongst themselves and security forces. In response, numerous governments employed so-called mano dura (iron fist) crackdowns that included widespread arrests and increasingly draconian laws.

*This article is part of a six-part investigation, “El Salvador’s (Perpetual) State of Emergency: How Bukele’s Government Overpowered Gangs.” InSight Crime spent nine months analyzing how a ruthless state crackdown has debilitated the country’s notorious street gangs, the MS13 and two factions of Barrio 18. Download the or read the other chapters in the investigation

The gangs were also invasive and predatory, occupying entire communities throughout the country and subjecting urban dwellers to extortion, murder, beatings, and sexual violence. In short, the gang problem presented a seemingly unsolvable puzzle for politicians, whose efforts to disrupt gang activity with force or to cool violence via backdoor negotiations failed to yield long-term results.

The latest attempt to deal with the gangs — dubbed a “war on gangs” by El Salvador President Nayib Bukele — has come in the form of yet another ferocious security crackdown. Following an egregious gang massacre in March 2022, his government enacted a state of emergency that gave the security forces free license to come down on the gangs with fire and fury.

Although parts of his strategies mirrored the hardline campaigns of his predecessors, the results are different: The gangs have all but vanished from the streets of El Salvador. In fact, the crackdown appears to have broken a cycle of death and violence that began as a US migration conundrum.

The gangs originated in California, formed by Central American émigrés, many of whom were fleeing violence and civil war during the 1980s. In the 1990s, as El Salvador was emerging from a brutal civil war, the US government shifted its policies to deport thousands of ex-convicts, many of whom were affiliated with the MS13 and Barrio 18. Once back in El Salvador, the deportees began establishing new criminal cells that mirrored the gang culture they had learned in the United States.

Over the following years, the gangs spread quickly, forming loose networks of cells operating under the banners of the MS13 and Barrio 18. Controlling certain territory opened the door to lucrative criminal economies such as extortion and drug peddling. It also led to bloody turf wars between these rival gangs, which increasingly targeted civilians and engaged in battles with security forces and other criminal organizations.

To combat the gangs, governments in the 2000s devised a program of heavy-handed security measures. Coined mano dura by the administration of former president Francisco Flores Pérez (1999-2004), and later super mano dura by his successor, Antonio Saca (2004-2009), these measures broadly relied on beefing up police presence and jailing gang members en masse.

Mano Dura Redux: The Price of Mass Gang Arrests in El Salvador

Despite some short-term reductions in violence, the campaigns failed to prevent the spread of street gangs or disrupt their main criminal activities. What’s more, the hordes of captured gang members began taking advantage of weak security and overcrowding in prisons to strengthen their ranks, create a more hierarchical and disciplined structure, and develop more organized criminal rackets from behind bars.

The gangs continued to wreak havoc into the 2010s, leading the El Salvador government to plot a different course. In early 2012, the administration of then-president Mauricio Funes (2009-2014) brokered a ceasefire with the MS13 and the two Barrio 18 factions, known as the Revolucionarios (18R) and the Sureños (18S). The government promised to transfer gang leaders away from maximum security prisons in exchange for cooling violence.

The so-called tregua (truce) quickly cut murders in half, but the gains did not last. Rather, the ceasefire unraveled in spectacular fashion, sparking brutal clashes between rival gangs and the security forces.

The violence peaked in 2015, when El Salvador’s annual homicide rate of 103 per 100,000 inhabitants made it the most violent country in the Western Hemisphere.

Since peaking in 2015, the country’s murder rate has been declining. This started during the administration of former president Salvador Sánchez Cerén (2014-2019), whose government launched a new offensive against the gangs and enacted strict measures to disrupt criminal rackets coordinated from behind bars.

The decline in homicides was substantial, falling by 50% between 2015 and 2018, though the murder rate stayed well above regional averages. Increased pressure from authorities also failed to disrupt the gangs’ widespread territorial control and extortion operations.

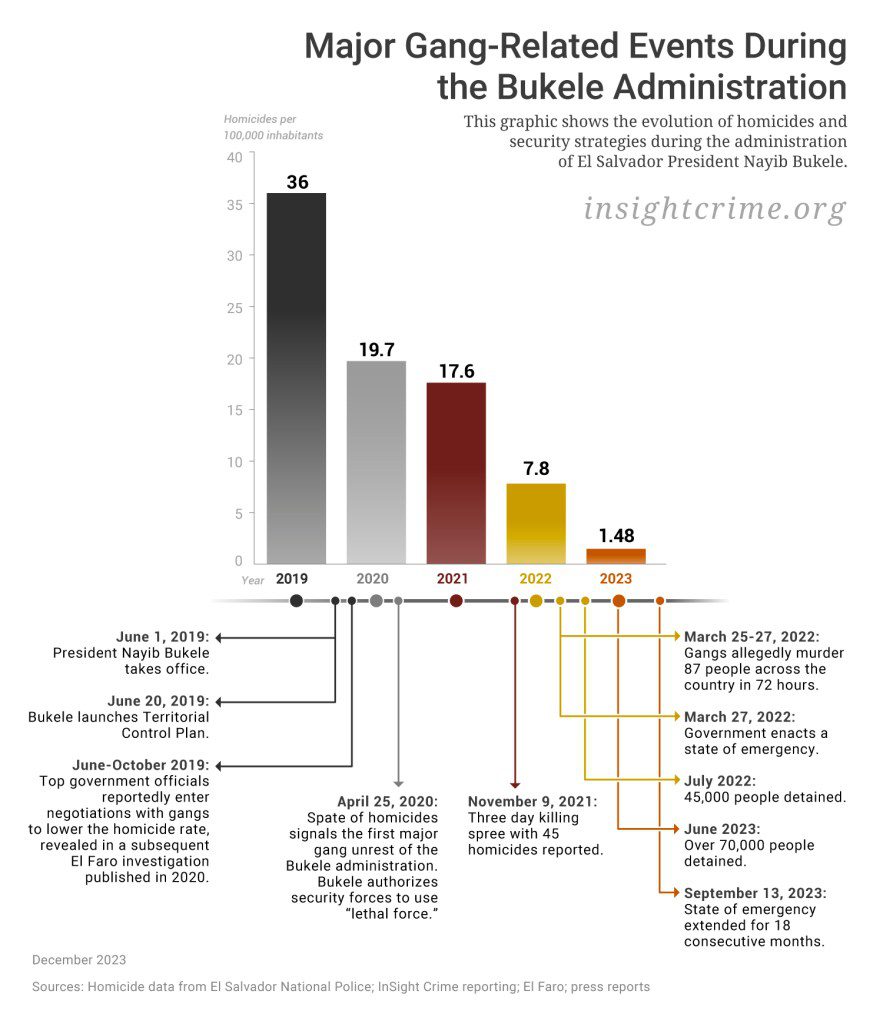

President Bukele took office in June 2019 following a landslide victory earlier that year. The start of his tenure saw a radical drop in murders, accelerating the trend that Sánchez Cerén started.

The Bukele government attributed the rapid decline in murders to the president’s flagship security plan. Dubbed the Plan Control Territorial (Territorial Control Plan), the strategy was poorly defined and mostly hidden from public view. Critics were quick to point out that key elements of the plan, including increased police patrols and more security forces on the street, mirrored those of previous mano dura campaigns.

Homicide Drop in El Salvador: Presidential Triumph or Gang Trend?

What’s more, just over a year into Bukele’s tenure, it emerged that some of his administration’s top officials had, in fact, sought negotiations with jailed leaders from the three main gang factions, trading prison benefits in exchange for their help lowering the murder rate.

The Bukele government repeatedly denied these accusations, instead leveraging the drop in homicides to boost the president’s popularity, help his party win a supermajority in the legislative assembly, and assist him in reforming the judicial system in his favor. But subsequent sanctions by the United States Treasury Department on two of Bukele’s interlocutors privy to the arrangement seemed to confirm the backroom deals.

Although by 2020 homicides had dropped considerably, the gangs still controlled territory and various criminal economies. And they were still able to rattle Bukele, using sporadic outbursts of violence to signal discontent with the negotiations or squeeze the government for further concessions.

One of those outbursts came during the final weekend of March 2022, when the gangs allegedly murdered 87 people across the country in just 72 hours. The bloody weekend sparked nationwide horror and marked a turning point.

On March 27, the country’s legislative assembly, acting on Bukele’s instructions, declared a month-long state of emergency, suspending constitutional rights and loosening rules on making arrests in an attempt to retaliate against the gangs.

The heavy-handed measures shared some similarities with previous government efforts, albeit with a crucial exception: The use of emergency legal measures, combined with Bukele’s influence over the three main branches of government, removed several checks and balances that had, during previous crackdowns, prevented state authorities from shifting mano dura into overdrive.

Dubbed the régimen de excepción (state of emergency), as of November 2023, the measures have been extended for 20 consecutive months. In that time, El Salvador authorities have launched a ruthless campaign of raids in areas with gang presence, arresting between 72,000 people and 77,000 people — over 1% of the country’s 6.3 million population.

The government claims most of those arrested belong to street gangs, but civil-society groups, religious organizations, and academics have flagged widespread arbitrary detentions amid more than 5,800 alleged human rights violations during the crackdown’s first year.

The indiscriminate nature of arrests makes it difficult to estimate exactly how many gang members have been detained. But information from El Salvador police intelligence reports obtained by InSight Crime suggests the majority of people arrested during the state of emergency are not fully-fledged gang members. Most are aspiring members and “collaborators.” In addition, by the government’s own estimations, there were over 21,000 fully-fledged gang members at large as of the end of September 2023, according to confidential intelligence reports accessed by InSight Crime.

Regardless, the controversial crackdown appears to have at least temporarily crippled the gangs, driving violence to record lows and leading Bukele to declare victory.

The crackdown has made Bukele immensely popular in El Salvador, and political leaders throughout the region appear increasingly keen to appropriate his strategies to deal with their gang issues.

But questions remain about the long-term feasibility of sustaining the aggressive crackdown, and whether failing to address the socioeconomic conditions that facilitated the gang’s rise in the first place could create space for these structures to regroup or mutate. Critics, and even some supporters of the state of emergency, also point to mass human rights abuses and arbitrary arrests, in addition to deplorable conditions in the country’s overcrowded jails, as possible detonators of future criminality.

The gangs, though battered and bruised, have not been fully defeated. And in the wake of past crackdowns, they have proved remarkably adept at adjusting to new realities at home and abroad.

*With additional reporting by Steven Dudley, Carlos Garcia, César Fagoaga, Bryan Avelar, Roberto Valencia, and Juan José Martínez d’Aubuisson